It was my tenth birthday. My family and I were going to celebrate with a trip to the city: visit Lincoln Park Zoo, walk along the Lakefront, and ride the ferris wheel at Navy Pier. But first, a quick trip to the hospital.

If my family was taking a day trip to the city, it usually included a stop at Children’s Memorial Hospital. At the age of two, my brother Maclain was diagnosed with leukemia, a type of cancer that affects blood-forming tissue. He was admitted to Children’s Memorial Hospital for treatment, a place my parents rarely let us visit if we could avoid it. Yet, it was my birthday, and my brother needed his check-up.

From the outside, the hospital was like none I had seen before. The large exterior loomed menacingly, and I felt small approaching, craning my head out the back of a minivan window. In my youth, the blinding white tile rose and towered like a city skyscraper, appearing sterile. I would try to count the rows of windows and concentrate hard on looking inside, wondering how many children there were and what brought them here, if they were all sick like my little brother.

Now, the once pristine tile is stained and weathered. In fact, half of the hospital is no longer standing.

“It was a landmark for over a hundred years and a second home to many of us,” said Dr. Elaine Morgan, who has worked with the hospital since 1975.

Earlier this year, Children’s Memorial Hospital was set for demolition. Now, in its place lays a wasteland of drywall, pipes and cracked tile.

Founded by Julia Foster Porter in 1882, Children’s Memorial Hospital started as an eight bed cottage at the corner of Halsted and Belden under the name Maurice Porter Memorial Hospital. The hospital was the first in Chicago dedicated to the care of children and pediatrics. The main Lincoln Park location on Lincoln and Fullerton was built in the 60s, where it remained until June of 2012.

“It was worse seeing the building looking dirty and not kept up,” said oncology nurse Maureen Haugen, who has been with Children’s since 1981. “That was harder than hearing that it’s being torn down.”

While Children’s Memorial Hospital was expanding, the building had no room to grow. Haugen describes working “elbow to elbow,” with crowded waiting rooms and outdated equipment.

“[We] outgrew the building in Lincoln Park and there way no way to increase the size at all on the footprint that [we] had,” said Haugen.

On Saturday, June 9, Children’s moved 150 patients to the newly built Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago on Chicago Ave in Streeterville. Accompanied by 30 Chicago Police Department (CPD) aides, along with 25 of the hospital’s own ambulances, CPD closed Fullerton from Lincoln and Lake Shore Drive for the three and a half mile move.

“It was just amazing, shutting down Lake Shore Drive and Fullerton just to get to see all the kids being carried,” said Haugen.” It was just really an amazing day and all the coordination and care that needed to happen in order to get it done.”

Bought by McCaffrey Interests, the vacant hospital was set for demolition.

“It’s obsolete,” said Dan McCaffrey, CEO of McCaffrey Interests. “The professional term is functional obsolescence.”

In real estate, functional obsolescence refers to a property that is unpractical, or undesirable. In the hospital’s place, the six-acre lot will feature a new consumer center complete with restaurants, parking garages, storefronts and 600 new residencies of luxury apartments and condominiums.

“The clinic waiting room was always full of patients and families that were talking and laughing and networking, and the new hospital clinic really prides itself on privacy,” said Haugen. “Even though… we all worked elbow to elbow, it in fact was a way that staff and patients and family got to talk and know each other well.”

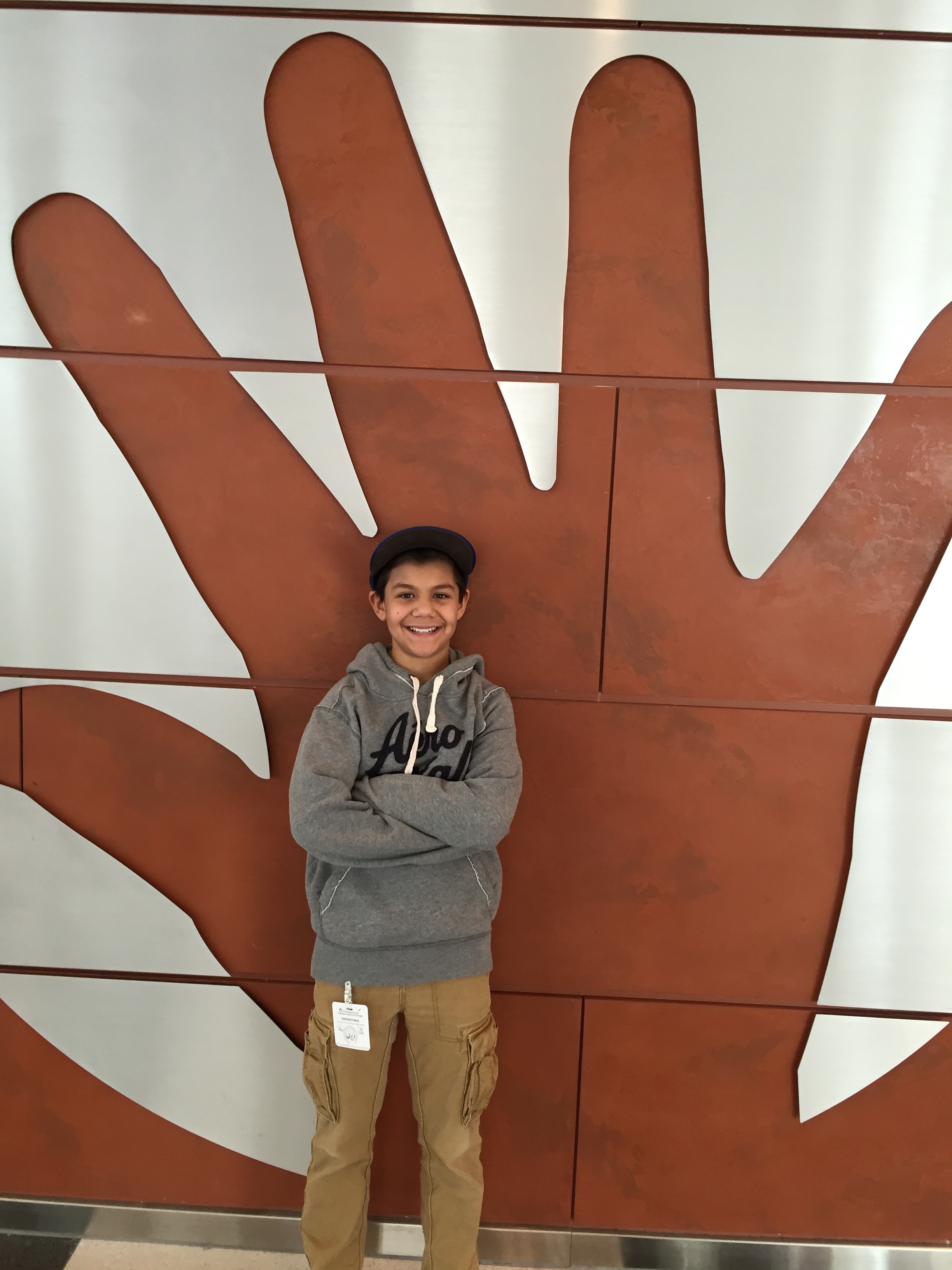

Children’s was its own community. As we waited for my brother’s blood count, my mother would chat with other families, sipping on McDonald’s coffee from the food court. My sister and I would spend our time in the children-friendly waiting room, equipped with crafts, board games and coloring pages. We interacted with other patients and families, sharing crayons or making Lego worlds together. I tried to be nice without being intruding, always taught not to stare, and to remember that we were guests. We were the lucky, healthy siblings.

“Downtown we are just part of a big hospital complex and have lost the unique identity of the old Children’s Memorial,” said Dr. Morgan. “ It was clear from day one that Lurie was a new entity not an old one reconceived.”

Ten years later, I walk past the hospital lot each day on my way to school. My brother is now nine years in remission, and the hours spent at Children’s Memorial Hospital feel like another normal, childhood memory. Time passes, and rubble now lays where there once was life. Soon the lot will be filled, revitalized by other citizens and young professionals beginning families of their own.

I call my brother as I pass the building. I ask what he thinks about the hospital being demolished. He said he can’t remember much besides patient waiting rooms, hospital masks and the emergency room. He tries not to think about it too much.

Plus, he said, the new hospital has free food and video games.

I hang up. The streetlights dance off the shattered glass, and a gaping hole exposes the skeleton of old patient rooms. Now, I can clearly see inside.

Sometimes, I imagine myself standing in the rooms again. I focus on coloring pages, McDonald’s coffee and white tiles. I focus on my brother.

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST