The prevailing wisdom behind film theory is that there is really no such thing as “reading too much” into a film. In analyzing a movie, pretty much anything goes. Whatever occurs onscreen—every plot point, every frame, every cut—can be taken as a deliberate move by the filmmakers to illuminate a certain theme or intention. Everything about the movie is fair game.

The Coen brothers have built their careers on a body of work that is not just immensely entertaining, but also evinces a thorough understanding of this holistic approach to film criticism. They understand that there’s more than character and plot to developing theme—there is also the fact that you are telling a story, and that fact can be toyed with and manipulated to further that theme. Their movies traffic in familiar themes of vengeance, moral judgment, and the folly of man, but they do so in completely unconventional ways. Almost less interesting about the Coen brothers’ films is what they are saying than how they say it, and it’s why their films fill the spectrum from devastating tragedy to belly-laugh hilarity.

So while No Country for Old Men is the bleak end of nihilism that manifests in hopelessness and tragedy, Burn After Reading is the goofy cousin that is concerned more with futility. It shares the same thematic DNA as No Country, but runs in the opposite direction. Burn After Reading is almost a defiant statement by the Coen brothers about the nature of theme, about the truly cosmic insignificance of events and the relationships between them. For all its twists and turns, it’s much easier to come out of Burn After Reading feeling like you were just played, and therein lies its genius.

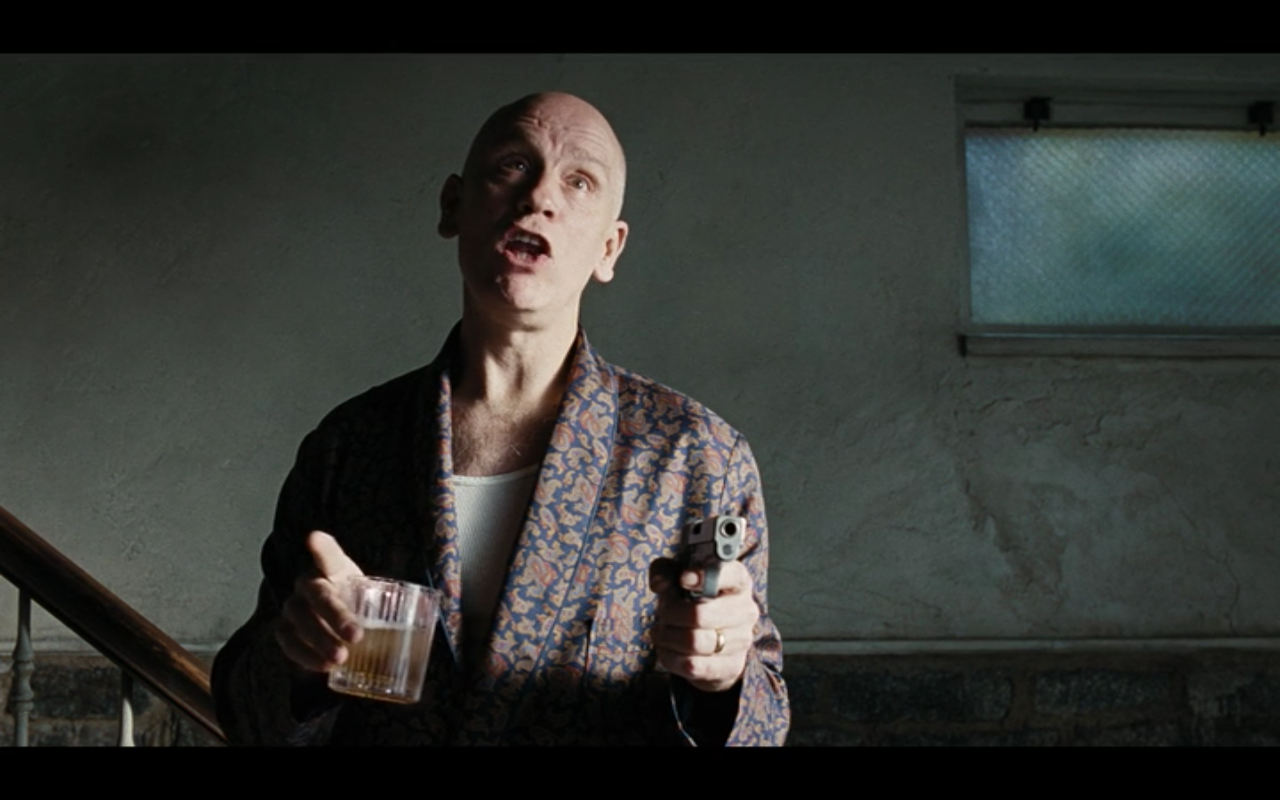

Analyst Osbourne Cox (John Malkovich) is being let go from his job at the CIA because of his alleged drinking problem (an allegation he refutes but ultimately goes on to prove handily). In his ensuing bitter rage, he resolves to finally pound out that memoir of his, juicy with secrets that he has accumulated from his time as an esteemed government servant privy to classified information.

This crisis of identity links us to another crisis in his life, one to which he is not privy—that of his wife Katie (Tilda Swinton) and her affair with the greasy Harry Pfarrer (a perfect George Clooney). Katie plans to leave Cox for Pfarrer, and has a divorce attorney lined up to do so. At her lawyer’s suggestion, Katie downloads all of Cox’s files onto a CD so that she can be sure no stone is left unturned in the legal proceedings. When the attorney’s assistant loses the CD at a gym called Hardbodies, we meet the underdogs of the story: Chad (Brad Pitt) and Linda (Frances McDormand), the Hardbodies employees who recognize the files on the CD as classified and embark on a plan to blackmail this Cox fellow for their own personal gain.

If this all sounds like a little much, it’s supposed to. Every element of these proceedings is so exaggeratedly cartoony that it’s never clear what kind of movie you’re watching, and at the point that the staff of Hardbodies picks up the ball and runs with it, the movie devolves into a frenetic hodgepodge of clichés that even the characters are falling for. At one point, Chad and Linda go to the Russian embassy with their coveted documents on the basis that Russians seem like the people you go to in geopolitical events like these.

The breathless score and grainy visuals are reminiscent of the espionage capers that the movie seems to parody, while the unwinking dimwittedness of the characters makes us question whether or not they are even supposed to be laughed at. When Hardbodies, its bumbling staff and their workplace dramas are introduced, you suspect that the film might be just a comedy of errors, fueled by the kind of socially maladjusted characters that usually populate an Apatow movie. But just as you’re starting to reconcile these contradictory parts, the movie takes a decisive sharp turn that proves it belongs to no singular genre (and I suspect that anyone who’s seen it knows exactly what I’m referring to here).

Burn After Reading commits to its twisted narrative with such jaw-dropping intensity that, even though it can be logically parsed out from beginning to end, you will nevertheless be left wondering what the hell you just watched. This is where the Coen brothers’ signature brand of post-modernism comes into play. The Coen brothers’ movies, for as superficially entertaining as they certainly are, are also rarely without commentary on preceding cinematic form and the nature of storytelling. Think of the bizarre circular narrative of Inside Llewyn Davis, and its relationship to Davis’s perpetual misreading of own role within the music scene; the very construction of his story is essential to understanding its defining theme. So, too, does Burn After Reading rely on its contrived spy movie plot, its zigzagging narrative focus, and the viewer’s own knowledge of the Coen brothers’ historically dimwitted protagonists to make its point. So much happens within its 90-plus minute runtime that you spend most of the movie trying to race each narrative strand to some satisfying conclusion.

The Coens have such artful mastery of tone that they will seed an entire character that you later realize was only there to divert your expectations. As soon as we think we have a grip on what greater narrative purpose a character is serving, the character is systematically disproven as having any central role in any story whatsoever. It’s brutal to our sense of storytelling and the constructs of morality that we typically impose on cinematic narratives.

And all of this would be utterly disorienting and borderline infuriating if it weren’t executed with absolutely gleeful mastery. This movie boasts an ensemble that includes—(inhale)—George Clooney, Brad Pitt, Tilda Swinton, John Malkovich, Richard Jenkins, Frances McDormand, J.K. Simmons, David Rasche, and even Dermot Mulroney in a bit of brilliant meta-casting.

It’s almost as if the cast list itself, stocked with distinguished character actors, is meant to induce some kind of expectation of lofty meaning and import, as if we could parse out what the whole thing is really about with just a character list. But as if to prove that the Coens are above this—and more likely, to assist us in gleaning some morsel from the movie’s black heart—the story of classified files and infidelity and Russian blackmailing periodically cuts away to the CIA office that is surveilling these proceedings. Whereas the government in most espionage movies represents some sort of monolithic authoritarian figure, impenetrable and ominous, here the trope is inverted to offer us a mirror of our own reactions, like a cutaway to a commentator during a sports game. It’s an ingenious bit of writing that refreshes us, allowing to come up for air from the swamp of this rapid-fire black comedy.

In short, while Burn After Reading has proven to be among the Coen brothers’ most fiercely divisive films, it merits a one-time watch for its pleasure factor alone. It’s meaningless, and that liberates us to soak in the humor of these richly drawn characters. Clooney’s gold-chained lothario, Pitt’s affably incompetent jock, McDormand’s endearingly self-deprecating go-getter are among the most colorful characters of these actors’ careers of colorful characters.

If the Coen brothers have historically trafficked in that high-minded realm of cinema where everything is allowed to mean something, then Burn After Reading represents a brilliant inversion of that reputation. By packing this black comedy with as many details, tropes, and plotlines as it can hold, they dare you to dig in. Not every movie with a nihilistic heart will be as perplexingly busy as this one, but undoubtedly none of them will be as good a time as Burn After Reading.

NO COMMENT