For my 20th birthday this year I received the gift of full hearing. After getting trial hearing aids from an audiologist, I heard sounds I never knew the world made: my shoes scraped against the carpet like steel wool, the air conditioning unit buzzed and rattled in the corner, rain pelted the windows like quarters on a tin roof. I heard my boyfriend’s voice reverberate through the doctor’s office with bass tones I didn’t know he possessed. I heard my own voice sing and realize that yes, my mom was right, I am basically tone deaf.

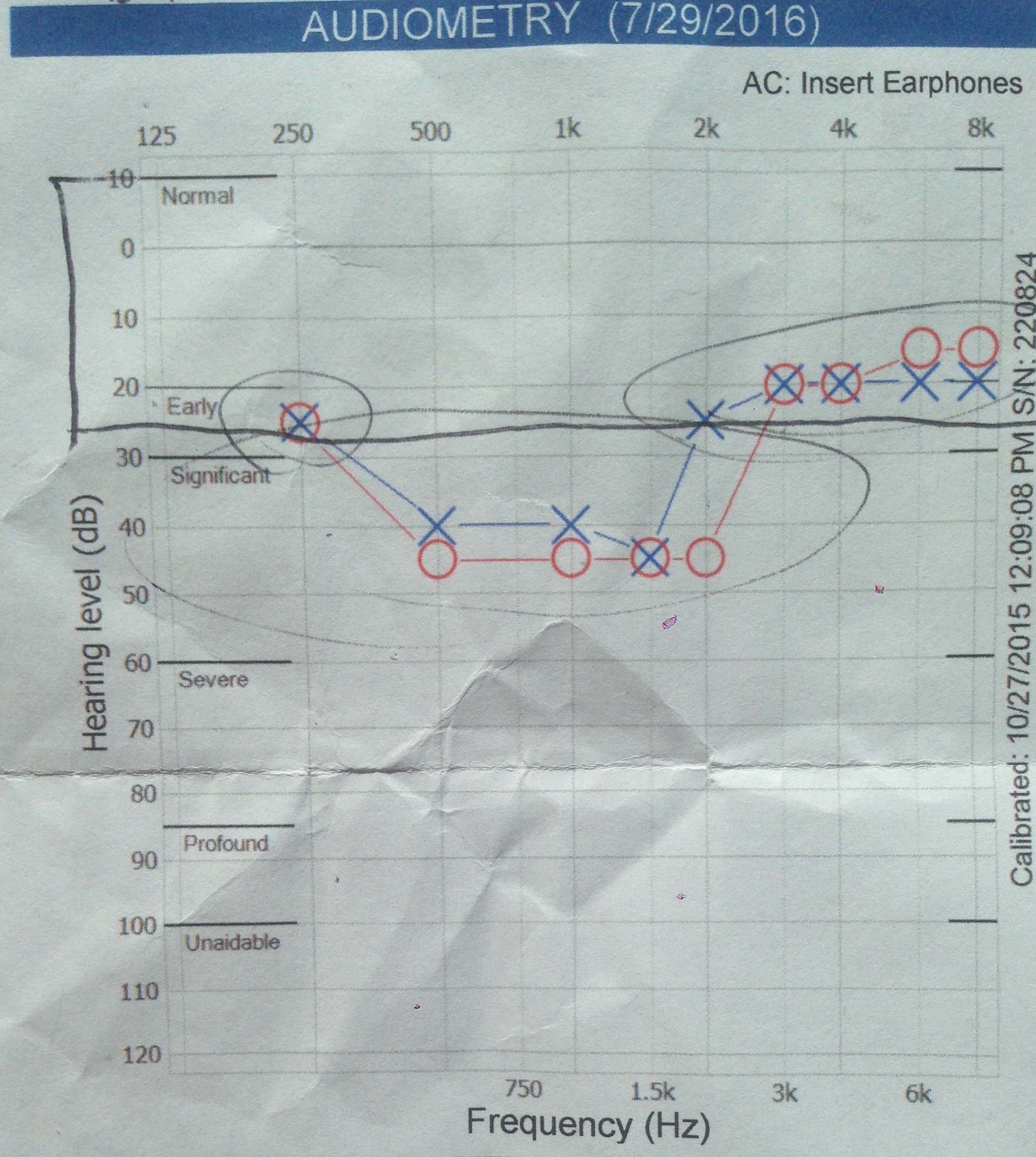

At the age of five I was diagnosed with a rare genetic hearing loss that doctors affectionately call a “cookie bite.” A cookie bite is characterized by a large dip in the center of an audiogram curve, which is where it records middle frequencies.

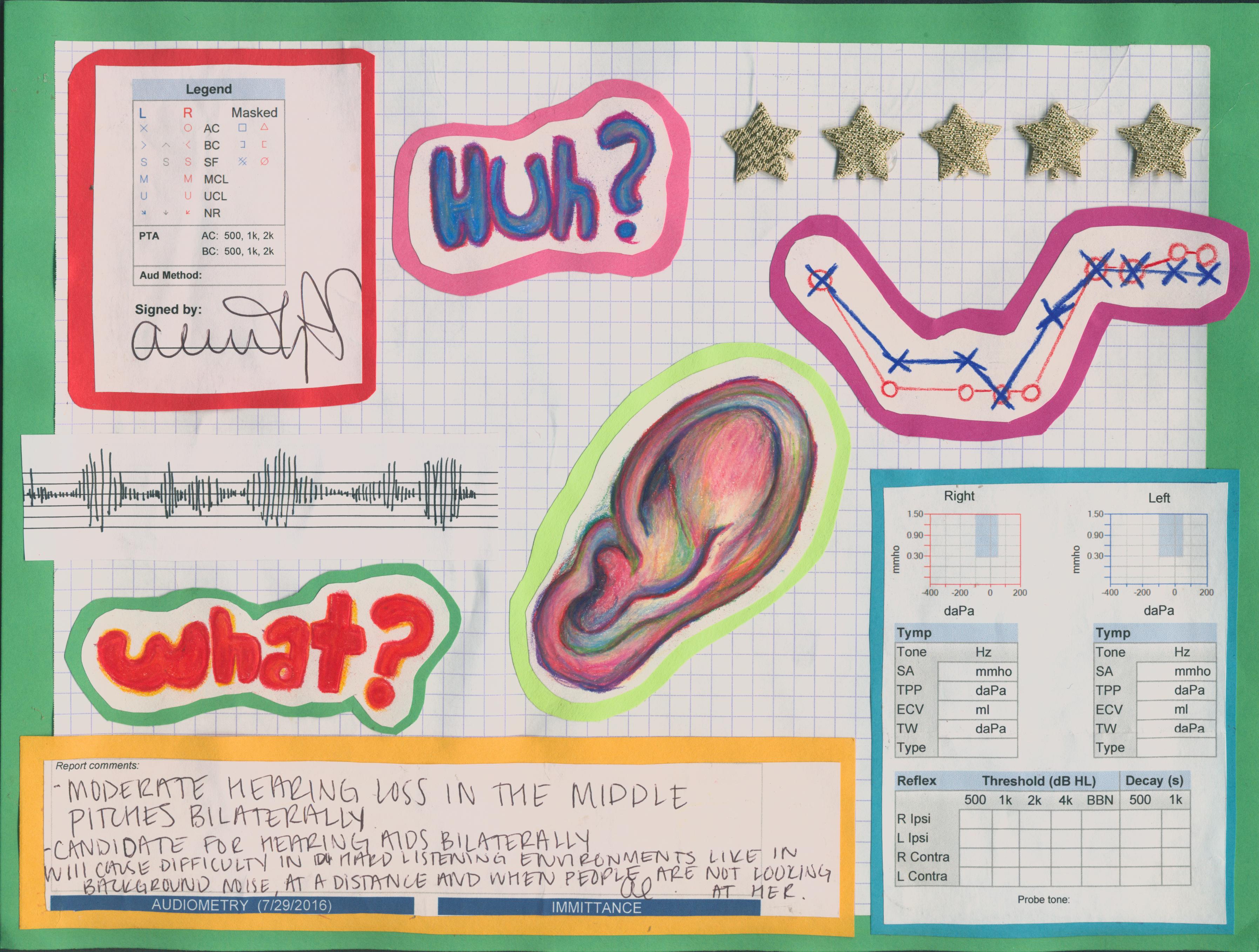

Kathryn’s audiogram (left) next to an audiogram of common sounds and consonants (right). Kathryn Teberg (left), Deron William (right).

The image on the right is an audiogram chart labeled with what noises and sounds are heard at what frequencies. That grey boomerang filled with letters is the middle frequency area. If you layer that on top of my own audiogram on the left you can see what sounds I struggle to pick up or just altogether miss. Nearly all of my hearing is in the early stages of loss, while the mid-range frequencies dip halfway into “significant”. They call it a cookie bite because it looks like someone took a bite out of my hearing range — but not out of my eardrum, a common misconception.

While my ability to hear both high and low frequencies is only slightly lower than the average American, I have to really stretch to understand noises that fall within that “mid-range.” Things like conversations, yells from the other room, whispers, and consonants are particularly difficult for me to understand without any kind of external aid. This means that not only do I completely miss a lot of sounds, but even when I do hear what you said, I sometimes don’t actually understand it. The noises you make jumble together and I can’t form the sounds into words. So I have to ask people to repeat themselves. I misunderstand directions and questions. I say “what” over and over and if I still don’t understand you, I just smile and nod and act like I got it because Lord knows it’s annoying to repeat yourself.

I learned to fill in the blanks and get by — to ask questions, pay attention to context clues and read lips and body language. Because of how hard it is for my ears to pick up whatever you are putting down, I have become acutely perceptive of silent forms of human communication.

Growing up, I frequently confused my name with my brother’s friend’s name: Patrick. My brother would yell for Patrick from across the house but I would chirp back in response instead. How could I get those two confused? Well, try it. Say Patrick out loud, and then say Kathryn. Focus on the similar vowel sounds. Because of my cookie bite, when I hear “Patrick” yelled from a distance my brain identifies the vowels, hears but doesn’t understand the consonants, and then fills in the blanks for me. So I think to myself, “huh, my brother is yelling at me from across the house and, wow, I really ought to respond.”

My hearing problem was a running joke for most of my life. When I misunderstood things, my brothers would lovingly blame it on the cookie bite. They imagined it as this cute, silly, harmless thing. And for about twenty years, that is how I thought of it too.

However, this past March I began to realize just how much of this hypothetical cookie I was missing. Upon returning home after a long day, David — my boyfriend at the time — and I could hear his roommate playing guitar and singing in the basement below us. I nodded along with the faint riff and looped drum beat while we untied our shoes in the dark. David began to laugh, but I didn’t know why.

“What’s so funny?” I asked.

“Matt’s lyrics, aren’t they hilarious?” he said, head down, pulling off a muddy boot.

“What lyrics?”

David looked up and, as if testing thin ice, asked: “The words that he is singing? The lyrics? Can you not hear him?”

I stretched my ears, closed my eyes and tried to focus on the noise. I sat still and waited for the sound waves to wash over me. But, alas, nothing.

“No. No I can’t — ” I whispered across the darkened room. We sat there for a while in our own silence and let the music fill in the space. David, I can only imagine, sat in a robust world of electro-pop rock laced with silly lyrics while I treaded the muddy waters of an underwater and unfinished bass-heavy EDM show. Only then did I begin to understand how much of the audible world I might be missing. If I couldn’t hear Matt singing in the basement, what else could I not hear?

It took me another month or so to actually call a doctor — and it seems silly now — but I was scared. Scared to find out how bad it was, as if not knowing the truth somehow made it different. Prior to this, I never really understood why people avoided going to the doctor to get screened for something, like a colonoscopy (other than the obvious for that one, I mean). And while David kept reminding me that I needed to go, finals came and went before I made an appointment. Finally, he sat me down to find an in-network audiologist. We made that call on speaker phone, together. And when they asked if I could bring in someone whose voice I was familiar with, he smiled and chimed in that he’d be there. Their next opening was July 29th. Incidentally, my 20th birthday.

I was, by at least a quarter of a century, the youngest person in the audiologist’s waiting room. The old women, wearing sweats and pearls, peered at me with beady eyes from behind bifocals. Like kids in detention, they wanted to know why I was there. A TV in the corner ran a slideshow advertising a landline telephone that transcribes conversations as they happen. So you can keep up with your grandkids! Posters around the room offered us patient patients trivia on baby-boomer rock stars. Did you know that Neil Young has tinnitus? And Phil Colins announced he would no longer tour due to an unspecified hearing problem? David and I waited in silence for the nurse to call my name.

The test was fast. After asking background questions and familiarizing herself with my childhood diagnosis, the doctor guided me into a sound booth and walked me through what to do and say. David sat outside of the booth with a microphone and a list of words. The doctor asked me to repeat back the words that David read to me “exactly as I heard them.” After that she played various noises, and I hit a button to indicate which ear I heard them in. Next she read full sentences and asked me to repeat them back as she adjusted the volume. Overall, I thought I had done pretty well!

When the tests were done she lead us to her office to explain the results. “Yes, the other doctors were right,” she said, “you should have received hearing aids as a kid, but considering the amount of hearing you lost, or, actually never had, you have been doing really well. You learned how to get by with less than the rest of us.” She gestured to David and herself. “While I highly recommend getting hearing aids, because you have done so well without them for the past 19 — 20 — years, you may prefer to not have them.”

She programmed the trial devices and slid them across her desk to me. David rested his hand on my shoulder while I put them in. I placed the main hub behind my ear and wrapped the clear wire around, and inserted the dome speaker into my ear canal. Initially, I heard only static, but then the crackle faded into clarity, like a camera refocusing on something way off in the distance.

Suddenly I heard the cars thirteen stories below me on Michigan Avenue honking through the July heat. At first I struggled to make sense of these new noises. My mind raced from one sound to the next, trying to figure out what the hell these things were, what they meant, and where they came from. I imagined a miniature version of myself sprinting all over the inside of my brain grabbing a hold of each new sound as one end of an electrical cord and then anxiously looking for an outlet to plug it into. Gradually I began to form meaning out of the static. David’s gentle voice rose to the top like cream billowing up from the bottom of a cup of hot fresh coffee; its familiar tones provided a sanctuary from the strange cacophony.

He took this video of me on Michigan Avenue after we left the office. Rain hit the sidewalk and cars honked. Busses screeched to a halt at lights and bikers raced by me. When we got home we did a side by side test of what listening to music would be like. I took the hearing aids out and played Aurora by the Foo Fighters — one of my favorite songs in high school — and then I put them back in and played the song again. I cried. I had listened to this song hundreds of times and never heard all of the instruments and backing vocals. It was like finding a new room in your childhood home that you never knew was there. You called this house home your whole life, you know what is inside each and every cabinet, you know where your mom stores the medicine, and where your dad hides the liqour. But then, one night you walk down the hallway and suddenly there is another door and you open it to find a whole other fully furnished room, with dust on the cabinets and a stained carpet and you know someone has lived there your whole life and you just didn’t know.

However, while the aids supplemented my subpar hearing, after a two week trial period I decided against getting them for keeps. Not only were they expensive (bare minimum $800 each) and easy to lose, they only made actually making sense of this world more difficult. Afterall, I had gone twenty years without ’em, getting by with having less, and I didn’t really need them. They were just one more thing to take care of and keep track of.

At my birthday dinner with my parents that first night I heard waiters drop forks on the other side of the restaurant and someone chew ice at the table behind me. Suddenly I had to cut through all this extra noise before I could even hear my mom’s voice across from me. Yes, I could hear more, but it didn’t help me form the noise into actual words and meaning. It felt like someone gave me more more straws to grasp at and no extra hands with which to do so. So I gave the hearing aids back to the doctor and returned, curiosity sated, to my underwater world of distorted sounds and blurry conversations.

Header image courtesy of Kathryn Teberg

NO COMMENT