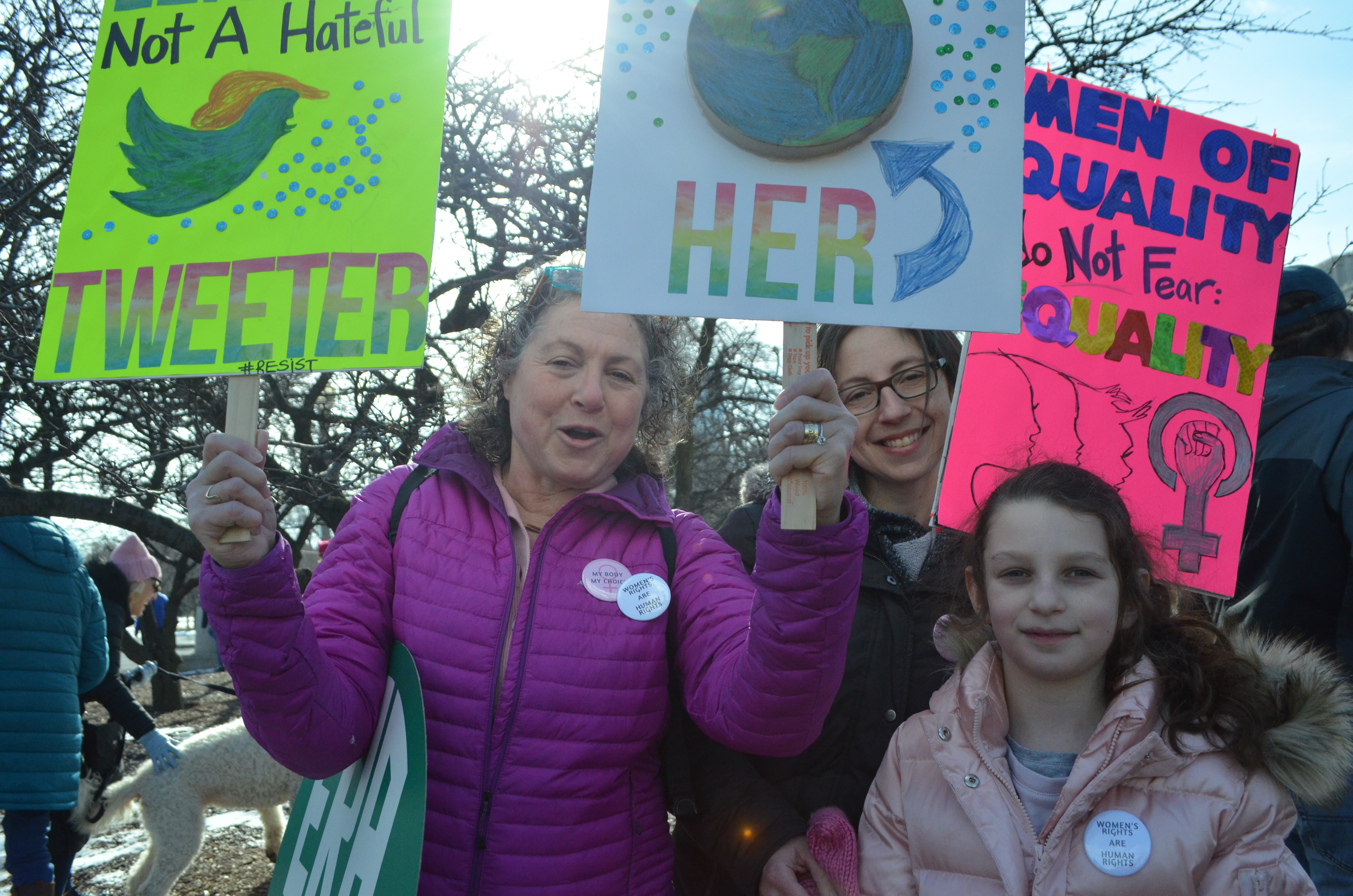

Even with a year’s worth of time between the two, the 2018 Women’s March began much in the same way as its 2017 counterpart — a ripple of pink weaving down Chicago’s main thoroughfares, bobbing silhouettes of posters in tow, figures clad in the light outerwear of a Midwesterner made to feel invincible by a mild January day.

They came by train, by foot and by car, filing out by the thousands down Michigan Avenue and into the fenced confines of Grant Park. This year’s well-attended Chicago rally, branded as a voting-centric “March to the Polls,” drew 50,000 more marchers — an estimated 300,000 in total — than the 2017 event. As our reporting team circulated throughout the crowd, we sought to get a sense of why attendees came to march this time around: After a year of tumult, what significance does the Women’s March hold in 2018?

In some regards, the imperative for action is clearer with a year’s worth of reflection. During last year’s rally, held just a day after the inauguration, the nascent Trump administration remained a foreboding but still vague idea, mired in the will-he-or-won’t-he potentiality of a bigoted reality star’s ascension to office. Hundreds of thousands took to the street; pundits made their predictions and Twitter hummed with anticipatory anxiety surrounding the impending four years. The president’s first executive order, signed hours after taking office and designed to lay the groundwork for repealing the Affordable Care Act, sent off an initial round of shockwaves — suddenly, the livelihood of millions hung in near-tangible balance. And so the first march became one of fear and revolution, an act of defiance in the face of uncertainty.

Marchers could only guess at what was to unfold over the next 12 months: the first so-called Muslim travel ban a week later, America’s withdrawal from the Paris agreement five months later, the right-wing terrorists in Charlottesville deemed “very fine people” seven months later. Just as significantly, the maelstrom of the #MeToo movement had yet to reach a national fever pitch — the Harvey Weinsteins and the Matt Lauers roamed their workplaces without scrutiny, free to harass and terrorize generations of women at will.

Given these circumstances, then, it’s fair — if a bit obvious — to call last week’s Women’s March a distinctly post-2017 event. The concerns murmured among the groups of women and allies in the rally’s sophomore run reflected these seismic sociopolitical shifts; they represented a swath of the voting block fed up with legislative threats to reproductive rights, immigrants and the LGBTQ community. Indeed, many of the people 14 East spoke to said this was their first time marching, spurred to action by the manifold indignities suffered at the hands of the Trump administration.

“We’re here to protest everything that’s being going on this year,” said one woman named Aneesa, who preferred to not disclose her last name. She and two friends wielded signs promoting universal health care, but also expressed anger about the sexual abuse revealed through #MeToo. “Even [things that have happened] in the media. You hear about things going on in Hollywood, for instance.”

The march is not without its failings, and organizers and attendees alike came under fire last year for muting the experiences of trans women and women of color in favor of a whiter, middle-class brand of feminism. And although organizers made a concerted effort to promote a variety of voices — featuring speakers like transgender activist Channyn Lynne Parker and a team of disability rights activists, among others — signs in the crowd, many of which relied heavily on iconography of vaginas and ovaries, remained steeped in the same hegemonic norms critiqued at the 2017 march.

Still, some attendees said they noted a positive change — at least on an organizational level — from last year to 2018.

“One of the videos they were playing up there like an hour ago, they just had a bunch of different faces who were running for office,” said Hannah Radeke, a DePaul senior, referencing a clip played at the event’s main stage. “I think that’s super important, because there were people of all different colors, all different orientations, I think that kind of presence is important to show.”

As an election year, 2018 carries a particular sense of urgency. Many women are running as first-time candidates, including Lauren Underwood for 14th District, Anne Stava-Murray for 81st District and Valerie Montgomery for 41st District.

Below, a dozen women and allies share why they marched this year.

Additional reporting by Madeline Happold, Francesca Mathewes, Megan Stringer, and Annie Zidek

Header image by Annie Zidek

Navigating Activism and Autism – Fourteen East

2 November

[…] you scroll through images on social media on the day of a Women’s March or a March For Our Lives, you will see so many people that they start to look like ants. Aerial […]