Every Friday night, members of an unofficial DePaul student organization sit around and wait for the phone to ring from students who are in need of contraception, pregnancy tests or lubrication. From 6 until 11 p.m., the members of Students for Reproductive Justice (SRJ) hang out near campus — but never on campus — waiting to get a message on Google Voice.

SRJ isn’t allowed to distribute condoms on campus. They can’t hang flyers in the Student Center, they don’t have an OrgSync account and DePaul largely ignores them — they aren’t considered a campus organization because of their mission and values. When SRJ began, they mulled over the idea of registering as an official DePaul club, but they knew if they were to try they wouldn’t be able to hand out anything controversial like condoms, pregnancy tests or lubrication — an aspect they still aren’t willing to give up.

DePaul’s Catholic values have kept condoms at bay, but the students who run SRJ want sexual health to be discussed more widely at the university. The opposing views and a university policy that prohibits the distribution of “medical or health supplies/devices” on campus that the university has deemed to be “inappropriate from the perspective of the institution’s mission and value” have kept SRJ officially off campus. The Office of Health Promotion and Wellness was not available for a comment before the time of publication.

“Health Promotion and Wellness is currently in the middle of an extremely busy time for our office,” director Shannon Suffoletto said. “I try and do whatever I can to meet the needs of those of you working on these important health topics, however, this week I do not have a staff member available to accommodate your request.”

Despite the university’s stance, students in need of condoms grab their phones and text the number that’s been distributed through fliers, social media and word-of-mouth. Privately, SRJ will provide anyone in need of their services with free contraceptives — no questions asked. The program was named Text Jane after an organization started in Chicago over 50 years earlier that echoed a similar message for reproductive rights.

The fight for rights over one’s sexual health and livelihoods isn’t a fresh battleground. The debate over what is legal and morally right has been tossed over legislative bills and dinner tables for years, with students at the forefront of the argument. With a similar fight to provide resources to their community while staying out of the limelight, the modern-day Text Jane is the aftermath of an era when women in Chicago called a private number and asked to speak to “Jane” in the hopes of terminating an unwanted pregnancy without risking their life, in a time before abortions were legal in the United States.

It all started in 1965. At the time, abortion wasn’t as easy to access as it is today. Abortion was largely illegal, but instead of unplanned pregnancy statistics spiking across the nation, desperate women turned to expensive and dangerous avenues in order to terminate a pregnancy. Women ran the risk that the physicians they were trusting could be completely unqualified or they could be charged an excessive amount of money for the procedure. The term “coat-hanger abortion” wasn’t a punchline to a middle school joke, but the reality that many women put themselves through in order to self-induce.

Over fifty years ago in the city of Chicago, a girl approached her sister’s friend, Heather Booth, about her unplanned pregnancy. She was scared and didn’t know what to do. Booth, a student at the University of Chicago at the time, was able to find a doctor who would perform the procedure. However, she knew something had to be done for the other women who were in a similar position.

Eventually, too many women were calling and looking for help. Booth gathered some other women, and together they started the Abortion Counseling Service of Women’s Liberation. This wasn’t a group that plastered their name on billboards overlooking the interstate. Rather, it grew through hushed whispers that came behind closed doors, spreading to the women who were stuck between a rock and a hard place and had nowhere else to turn.

The group’s mission reached the ears of women around the city, and eventually around the state. Access to safe and affordable abortions wasn’t a possibility before, but now women wouldn’t have to worry about bleeding out on a bathroom floor just to receive an abortion. Organizers for the Abortion Counseling Service manned the phones and waited for the voice on the end of the receiver to ask for Jane.

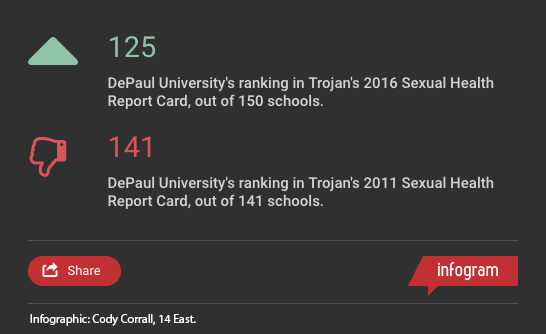

Seeing the rating that DePaul had gotten from Trojan in 2011 about campus sexual health, SRJ founder Amy Weidner realized there was a problem on campus. Trojan bases their ratings on the strengths and weaknesses of health centers on campuses, and DePaul didn’t offer enough programs, services and handouts available to make their way off the bottom of the list. Weider knew that despite DePaul’s low rating, students could emphasize sexual health themselves by offering education and materials on campus. The latest Trojan Report Card came out in 2016 and showed DePaul had moved up to 125 out of 140 overall in sexual health.

(Cody Corrall, 14 East)

Weider met Melissa Haggerty, a student at Loyola who started the first Students for Reproductive Justice. When the first SRJ was formed, the Loyola students decided to take matters into their own hands. Reaching out and talking with friends, Weider realized that there was a need at DePaul for reproductive rights and accessible protection.

Once the Center for Identity, Inclusion and Social Change shut down in August, Weidner knew it was time for something to be done. The founding members felt there was no active feminist or social justice group on campus that students could turn to. The founders wanted to bring reproductive justice to the forefront at DePaul, putting in their mission statement that they see “gender and racial violence, police brutality, mass incarceration, and the brutality of war” as “attacks on reproductive justice.”

Taking a firm stance on feminism, pro-choice laws and protecting every aspect of reproduction rights, the unofficial organization wanted to push past merely providing condoms on campus to creating a space for DePaul’s student body that promotes inclusivity and justice under the umbrella of the original reproductive justice mission.

Last August, Students for Reproductive Justice was born from both a lack of condoms and a space for healthy sex talk on campus.

Social media wasn’t even an inkling of an idea in the ‘60s, making the Jane Collective an immense undertaking for the founders of the underground abortion hotline. Every question and problem was addressed early on in the collective’s history. When a woman called, she was directed to a Jane member who could talk to them about their pregnancy and the possible procedure. The collective rented two apartments at a time in the city — one for women to initially show up at so they could wait, the second to be used for the actual procedure.

Jane initially set women up with doctors who could perform the abortions discreetly and safely. Over time, the collective started to rely on one doctor, nicknamed “Nick” by former member Laura Kaplan in her book “The Story of Jane.” Nick was seen as one of the most trustworthy doctors to the collective because he allowed members to remain present during the procedures, ensuring them of their client’s safety.

One member was trained by Nick to help perform abortions. She demanded he show her how, because in her words, he shouldn’t be able to hold all of the knowledge. As time went on, though, many started to question Nick’s qualifications as a doctor. He carried no license, and other doctors pointed out his discrepancies. The suspicion grew within the collective that maybe Nick had lied — perhaps he wasn’t a doctor.

People were shocked when the leaders finally announced that Nick had lied about being a licensed physician. They felt deceived, discredited and untrusting. Many left the group, losing faith in Jane and its mission. But this wasn’t about to slow them down. Through Nick and other physicians, the women who remained learned techniques to perform an abortion themselves.

Nick helped with some abortions, but by 1971 nearly all procedures were done by the Jane women. They lowered the prices for procedures and started offering pap smears for women who needed them. They were not only becoming well-known by women across the city, but also to the officials who wanted their practice to stop.

Signs at the 2018 Women’s March in Chicago. (Megan Stringer, 14 East)

Condoms in hand, SRJ brought the conversation about sexual health on campus. They chose to remain an unofficial organization after seeing the way that Loyola’s administration, another Catholic university, handled the original chapter. Loyola’s SRJ was not allowed to become a campus organization when they first formed. However, the founders at DePaul still wanted to be a part of campus life. At the beginning of the new school year, they were passing condoms out to students as they made their morning treks to class. DePaul’s Office of Health Promotion and Wellness quickly ended the morning campus handouts due to a strict university policy.

According to SRJ, the university told the new organization of their policy, titled “Restrictions on Public Distribution of Inappropriate Health and Medical Devices/Supplies.” This policy allowed for the university to effectively put a stop to the ‘condoms on campus’ crusade that SRJ took on, but it’s also a rare one to be on the books at a college campus. As of 2011, the most recent data available, approximately 84.9 percent of all schools distribute condoms to students, but most faith-based universities do not. Both Providence College and Marquette University explicitly state that they do not hand out condoms. So while DePaul may be in a minority by not offering condoms, they are on par with many religious schools across the country.

Regardless, it hasn’t slowed SRJ down. When they first made their appearance in fall quarter last year, they started with a Text Jane initiative. Named after the Jane Collective, SRJ set up a Google Voice number for students to call if they needed a condom late at night. It became more popular than they realized, with students even asking if they were around over winter break, according to founding member Jenni Holtz.

Though known for their free condom distribution every Friday night, SRJ takes all forms of sexual health into account for students.

“I think the appeal with Text Jane is that we offer more than condoms,” founding member Charlotte Byrd said. “We offer internal and external condoms, pregnancy tests for free, lube and dental dams as well. So it’s not just a condom that fits someone’s perhaps preferred sexual activity, but also anyone who is involved in any sexual conduct.”

As time went on, SRJ realized that DePaul students needed more than just a condom after a date. In January, they helped form a counter protest against the annual March for Life with other DePaul organizations. At the same time, the students are also in the process of creating a self-defense class for students and those in Chicago, and a space for sexual assault survivors to talk and find help.

Weider says the organization “grew from caring about just STIs and STDs and sexual health on campus, to being about reproductive justice as a whole.”

SRJ has grabbed the attention of those around them. They receive condoms and donations from a private donor, the Howard Brown Health Center and Catholics for Choice. They also won the best campus organization award from Bedsider, an online birth control support network. In September 2017, classes hadn’t been in session for a month when SRJ received a grant from Bedsider that has allowed them to keep everything free — and accessible — to students who need them.

“Bottom line, we encourage the healthy sexual lives of all people and the access to have safe sex,” Byrd said.

The Jane Collective ran for a number of years, right under the noses of the Chicago Police Department. They always stayed one step ahead, never quite got caught and continued to help as many as 10 women a day, four days a week.

Eventually in 1972, two women went to the police and said their sister-in-law was planning to get an abortion and they knew the organization that was planning to help her. Two homicide detectives traced the women in the group and found the collective in a South Shore apartment. They arrested seven of the members and took the patients who were waiting for an abortion to the hospital.

While in the police van, one member pulled a stack of cards out of her purse containing patient information. They took the part of the paper that held names and addresses, and ate them to avoid police tracking down the women who had received, or were going to receive, an abortion.

The women who were caught were indicted and released on bail. While awaiting trial, the Supreme Court ruled in the 1973 decision Roe v. Wade, and abortion was made legal across the country. Women were able to legally access abortions by licensed doctors, and the need for Jane no longer remained. With the decision, the charges against the Jane members were dropped.

The members all went on to live their lives. Some became activists, while others continued with their previous careers, had children and hoped that their services would never be needed again.

SRJ continues the battle for safe sex and safe abortions — no matter the social class, economic status or previous life choices of those who seek their services.

“When people hear ‘reproductive justice’ they think it’s just about condoms and just about women,” Holtz said. “But the term reproductive justice is so much broader than that. Basically, it understands that anything that is a threat to reproductive rights is a threat to the community.”

As they continue to grow, members work to push activism into the community. Weider noticed many students will say reproductive rights matter to them and they talk about how they want to help bring supplies to other students or get the university to change its stance. But when it comes time to organize, there aren’t students there to help back them up. For SRJ, pushing their members to get involved and show they care in person, and not just on social media, is a part of their ultimate goal.

“A big thing about being [at] a Catholic university is trying to shift the narrative a little bit, because you get a lot of ‘I care about these people’ but not a lot of actual caring,” Weider said about student activism. “It’s a lot of talk but no action.”

Despite the struggle to work around university policies while bringing safe sex resources to DePaul’s Catholic campus, SRJ continues to open their doors for anyone no matter the situation. They are active every Friday night responding to Text Jane messages, and setting up spaces for people to talk about every aspect of reproductive rights on campus and in the community.

53 years after the Jane Collective started in Chicago, SRJ continues to organize the fight for people to have a say when it comes to their bodies. They are the modern-day Janes; their goals of creating justice aren’t too far off the mark from that University of Chicago student who wanted to help a woman find an abortion.

“We’re here for you,” Weider said. “If you’re needing anything, if you need a feminist space for any reason, we’re here for you and we’ll support you.”

Header images by Cody Corrall and Annie Zidek.

Three DePaul Groups Mobilizing Around Women’s Issues – Fourteen East

8 March

[…] dental dams, lube and pregnancy tests to those on campus. Weider said the club got this idea from the 1960’s Jane Collective, a service in the pre-Roe v. Wade era that granted illegal […]