Bert Berrios was 12 years old when six older men dragged him into a dark room and beat him for three minutes. He covered his face and did his best to dodge each punch. Finally, the timer went off. The beating was over. Bert Berrios was officially a Latin King.

Ronnie Carrasquillo, better known as “Mad Dog,” was prominently known as the leader of the Logan Square-based Imperial Gangsters. He shot and killed Chicago police officer Terrence Loftus in 1976 just months after his 18th birthday.

Berrios and Carrasquillo lived together in medium security Dixon Correctional Center for 10 years. Berrios left after serving 21 years; Carrasquillo has served 41 years of his 200- to 600-year sentence.

Both now are members of prison ministry Radical Time Out, a 27-year-old Glen Ellyn not-for-profit that offers prisoners and ex-cons services ranging from social support to psychological counseling to an introduction to the Christian faith.

Radical Time Out is a prison ministry that serves anyone who has been impacted by incarceration, or those who have an interest in prison ministry. Although not every member finishes the 15-month program within Radical Time Out, 80 percent of those who do never return to jail or prison.

The organization can be described with five C’s: Color, Class, Crime, Culture and Crisis. Its motto is, “RTO is not a way of doing church; it’s the way to be the Church, namely by praying radically to love radically.”

Every Thursday evening, the group meets at the Glen Ellyn Bible Church at 5:15 p.m., where founder Manny Mill leads the group in prayer, serves a free dinner and recognizes a pastor of the week. The most moving portion of the whole meeting is given through the testimonial by one of the Radical Time Out members who has recently been released from prison. Each testimonial draws upon the individual’s relationship with God and their religion as it applies to their criminal background.

Berrios and Carrasquillo both grew up in Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood, contrary to popular belief that Carrasquillo grew up in Logan Square because he was known to be the leader of the Logan Square Gang, Imperial Gangsters. Carrasquillo says that he spent time in the area, but his home was in Humboldt Park. Berrios was born in the same year that Carrasquillo was incarcerated and spent his childhood at the Catholic church that Carrasquillo’s family attended. By the time Berrios made his way to Dixon, Carrasquillo knew who he was and took him under his wing.

While spending those years together in Dixon prison, both Berrios and Carrasquillo started to study the Bible together.

Their coming-to-Jesus moment stemmed from the work of Mill, an ex-con who served a three-year sentence, starting in 1986, for interstate transportation of forged checks. Mill is the founder of Radical Time Out and he leads the group in ministry every Wednesday evening.

Mill’s mission is to end recidivism. That’s a big task in Illinois, where over 45 percent of inmates return to prison.

That costs taxpayers $40,987, on average, for the arrest, adjudication, conviction and punishment of a conviction and will total a whopping $16.7 billion over the next five years if it stays the same, according to a summer 2015 report by the Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council.

The average cost associated with one recidivism event is $118,746. Taxpayers cover $40,987; $57,418 of the cost is borne by victims who have been deprived of property, incurred medical expenses, lost wages and endured pain and suffering; and another $20,432 comes from indirect costs in foregone economic activity, the report says.

Berrios, who has been a free man for a year as of February 16, 2018, remembers his testimonial like it was yesterday.

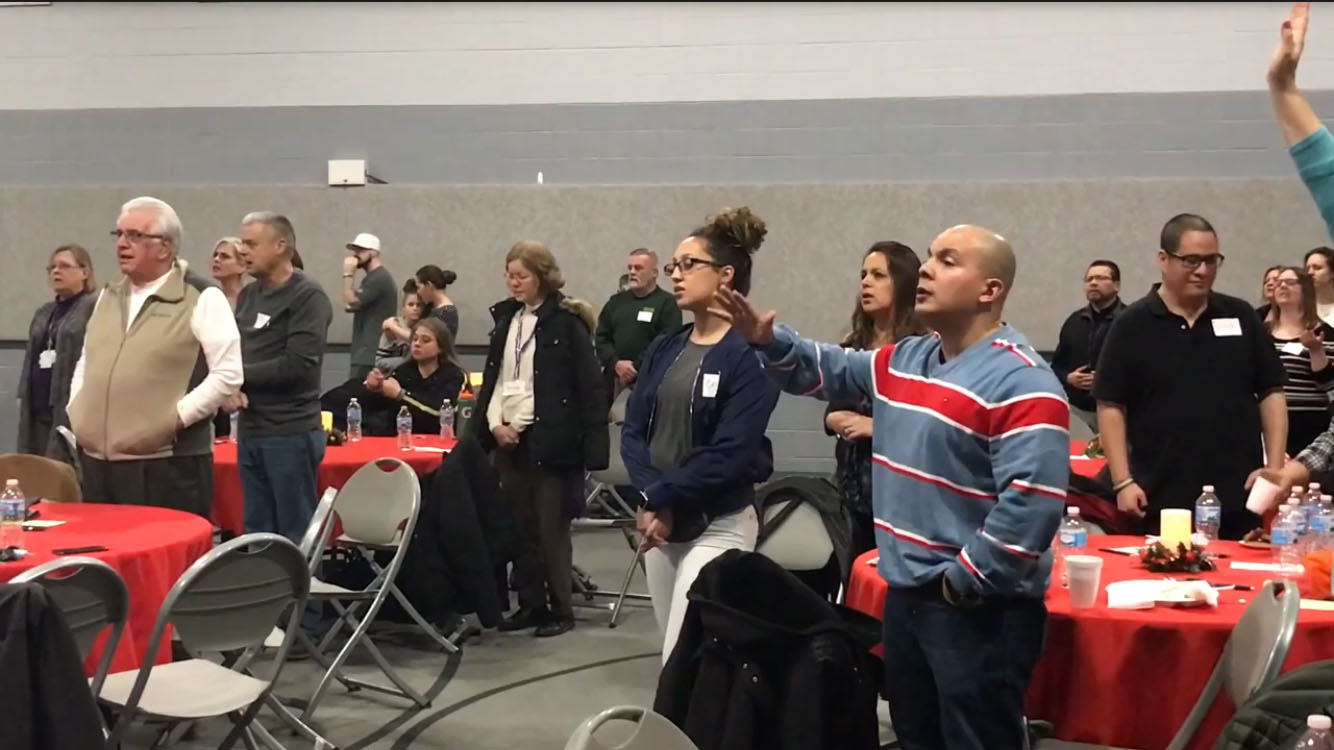

“The whole place was packed and I remember people squeezing into tables,” said Berrios. “I was honored that so many people wanted to hear my story and I was blessed to be there to tell it.”

Berrios attending a Radical Time Out meeting. (Ally Pruitt, 14 East)

Carrasquillo, who still resides in Dixon prison, is unable to physically be at Radical Time Out, but with the help of his sister, Deyra Mercado, he listens in every week.

Mercado receives a call from Dixon on Thursday evenings at 6:30 p.m. She answers, and brings the phone up to the front of the room, where the phone sits on the podium. Carrasquillo then hears everything said by the pastor, from the sermon, to the songs, to the testimonial.

Mercado was 7 years old when her half brother went to prison. Her family never gave specific details about the incident until she was older, but as a teenager, she began her quest to rekindle her relationship with her brother and with her faith.

Carrasquillo was sentenced in front of Judge Frank Wilson. Ten years after the sentencing, it came out that Wilson took a $10,000 bribe to acquit Harry Aleman, a mafia hit man, just five months before his trial. Wilson later died by suicide.

Carrasquillo is now working to appeal his conviction due to this unusual circumstance.

“This place sets you up for failure,” said Carrasquillo. “I’m the guy who pushes guys to go to school, to read the Bible, and I try to set them up for success in the midst of the chaos.”

Carrasquillo says faith is what motivates him and allows him to have a positive attitude.

“Things will not change unless we have faith that has a heart, a pulse, a faith that has life in it. A faith with legs so it can move; a faith with ears to hear, a mouth to speak; a faith with arms to reach; a faith that is so intense inside you it flows as if a cup runneth over.”

Mercado talks to Carrasquillo every week and visits him whenever she can. She says that throughout it all, her brother has been the most positive person she knows.

“It can be hard sometimes when we go to court and we hear bad news. But my brother and I have talked about his purpose,” said Mercado. “And he often says that maybe the reason God put him behind bars is so that he can change lives, starting with the people who need it the most.”

Berrios says Carrasquillo takes the new guys under his wing and encourages them to take solace in religion. Carrasquillo reads the Bible every day and says he grows closer to God.

Berrios is also a member of Midwest Bible Church, where he leads his own prison ministry. He was given permission from Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart to reenter Division Nine of Cook County Jail as a parolee to preach the Bible, something hardly ever granted permission.

Carrasquillo had his prayer journal published by Lynette Santiago, member of Rebano Church located in the Humboldt Park neighborhood of Chicago, and his bible study book, “The Art of Prayer,” published by Dr. Ruth Mercado, pastor of Rebano Church. He has also earned his bachelor’s degree in theology studies while inside Dixon Correctional Center.

Carrasquillo said, “For the past 30 years and at each facility that God has blessed me in, I have influenced numerous individuals to quit the gang life and serve our Lord, Jesus Christ. In the last 15 years, my function has been ministering to the youth, families, friends and immediate family. I am a walking ministry, my most prized accomplishment.”

With more than 2.3 million prisoners in the United States today, the issues of our criminal justice system remain prevalent, now more than ever. Mill says religious connection can be a serious factor in this needed change. His ministry, Radical Time Out, is known to be a bridge between churches and ministry partners with former prisoners, families of the incarcerated and those involved with the justice system.

Header image by Ally Pruitt

NO COMMENT