It’s fall in Chicago and the city is colorful — at least compared to the monochromatic geometric blur of the skyline mere months ago. The air is thick with moisture, greenery is itching to fade into yellowy browns and the streets are decked out with blue and red as a sign of Cubs team loyalty. But even brighter are the city’s murals, noticeable shots of color that fade and change just like the weather. Chicago’s public art has a unique history, aesthetic, community relationship and appeal that changes our landscape.

One of DePaul art history professor Mark Pohlad’s favorite murals lies beneath the Metra platform at the intersection of Lincoln Avenue and Addison that depicts firefighters in remembrance of the September 11th attacks, which he saw everyday when driving his kids to school. “I think a lot of [Chicagoans] have this experience, but I usually see them when I’m not expecting them, even though I’m like, ‘Oh, that’s right, this is here,’” said Pohlad.

The mural memorializing September 11th firefighters shows some wear on Lincoln Avenue (Meredith Melland, 14 East).

Shimashi Dammalage, a junior studying film and television at DePaul, has always been curious about murals, but was especially intrigued when she saw a work of JC Rivera’s “Bear Champ” series at her old elementary school, The Nettelhorst School in Lakeview. The yellow, pouty-faced “Bear Champ” can be spotted anywhere from taco shops to warehouses with trademark red boxing gloves and small three-tonged crown.

“I love finding murals around Chicago, whether it be for having photoshoots, to find out what it means or why it was painted there, or just to observe them,” said Dammalage.

Artist Matthew Hoffman, also known by his moniker heyitsmatthew, was drawn to public art because it could physically affect a community and combine his interests in typography and woodwork.

“I love making things that incorporate in people’s daily lives that offer positivity as well,” said Hoffman.

Chicago’s history with murals is likely as long as most other American cities – around 120 years. “I think the earliest murals, which is to say around 1900 or so, were for the interiors of buildings, and they were kind of decorative,” said Pohlad.

During the Great Depression, Roosevelt’s New Deal started a series of public works that included public art projects in places like post offices and schools, according to Pohlad. Modern murals as we know them now grew out of community expressions in the Civil Rights Era.

“The great era of public murals starts in Hyde Park and on the South Side with Black pride imagery, and Mexican pride after that in the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s,” said Pohlad.

This kind of bold and easily accessible art fits with Chicago’s artistic vibe, according to Pohlad. “From the ’50s onwards, [Chicago is] thought to really like funky, cerebral, graffiti-ish, recognizable art . . . it’s a blend of like surrealism but also low, common sources like comic books and graffiti and outsider art.”

He notes that Chicago murals retain both a playfulness and a physical largeness that fits with the city’s other public art works and architecture, including the Picasso statue, the Bean and even the Ferris wheel from the World’s Fair period.

This piece by French artist Kashink brightens up Wabash Avenue (Meredith Melland, 14 East).

Hoffman first discovered a passion for public art when he moved to Chicago in 2002 and started following the Wooster Collective, a blog that showcased different art around the city every day. He made a few stickers with a simple message, “you are beautiful,” which took on lives of their own once out in the city. The “You Are Beautiful” Project has multiple large installations in different neighborhoods, most recently on the side of the Cards Against Humanity headquarters in Lincoln Park.

“We get a lot of people that come by and are like, you know, “I’ve seen this everywhere and I had no idea what it was,” and to me, that’s perfect,” Hoffman said.

There are a few murals to spot in Lincoln Park, but one of the most visible is St. Vincent de Paul staring out from the side of McCabe Hall. Created by Mark Elder and a group of students, the Vinny mural features portraits of students, making it an example of a mural that is connected by community.

Down the South Loop’s Wabash Avenue near DePaul’s Loop campus, murals are both tucked away and out on display. This area between Michigan Avenue and State Street is the main area for the Wabash Arts Corridor, a non-profit that was started at Columbia College Chicago in 2013 by Mark Kelly, now the commissioner of the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE).

“It’s kind of this ever-expanding urban gallery,” said Sydney Pacha, the graduate projects manager for the Wabash Arts Corridor.

Each year, WAC approaches Chicago and international muralists to participate in their public arts projects, which Pacha describes as “an ever-rolling process” that has a general theme. Some of past years’ works include the billboard bubblegum moose and the “Harmony” banner near Green Line tracks. Though WAC is housed at Columbia College Chicago because Kelly worked at Columbia, WAC is not funded by the university and fundraises for every individual project. Pacha said a WAC mural can cost between $10,000 and $30,000.

In addition to price, murals can be seen as only surface-level beautification of Chicago streets.

“Some people resent a mural or art or gardens if other kind of basic life needs are not met. So it’s like if housing is crumbling, why have a mural?” said Pohlad.

But what is most notable about these public works of art is they can be ever-changing and temporary — adapting to the whims of the weather and city officials. Construction and development obstruct walls and spaces that were once easily viewed from street level or create rubble and make areas less viewer-friendly.

“I know that our really big woodpecker mural from Collin van der Sluijs is going to be covered in the next year or so because they’re building a building next door,” said Pacha.

Pacha notes that one Hebru Brantley “Flyboy” mural put up by WAC was covered up by another building, and even the well-known “Bear Champ” was recently flagged as graffiti in Lakeview.

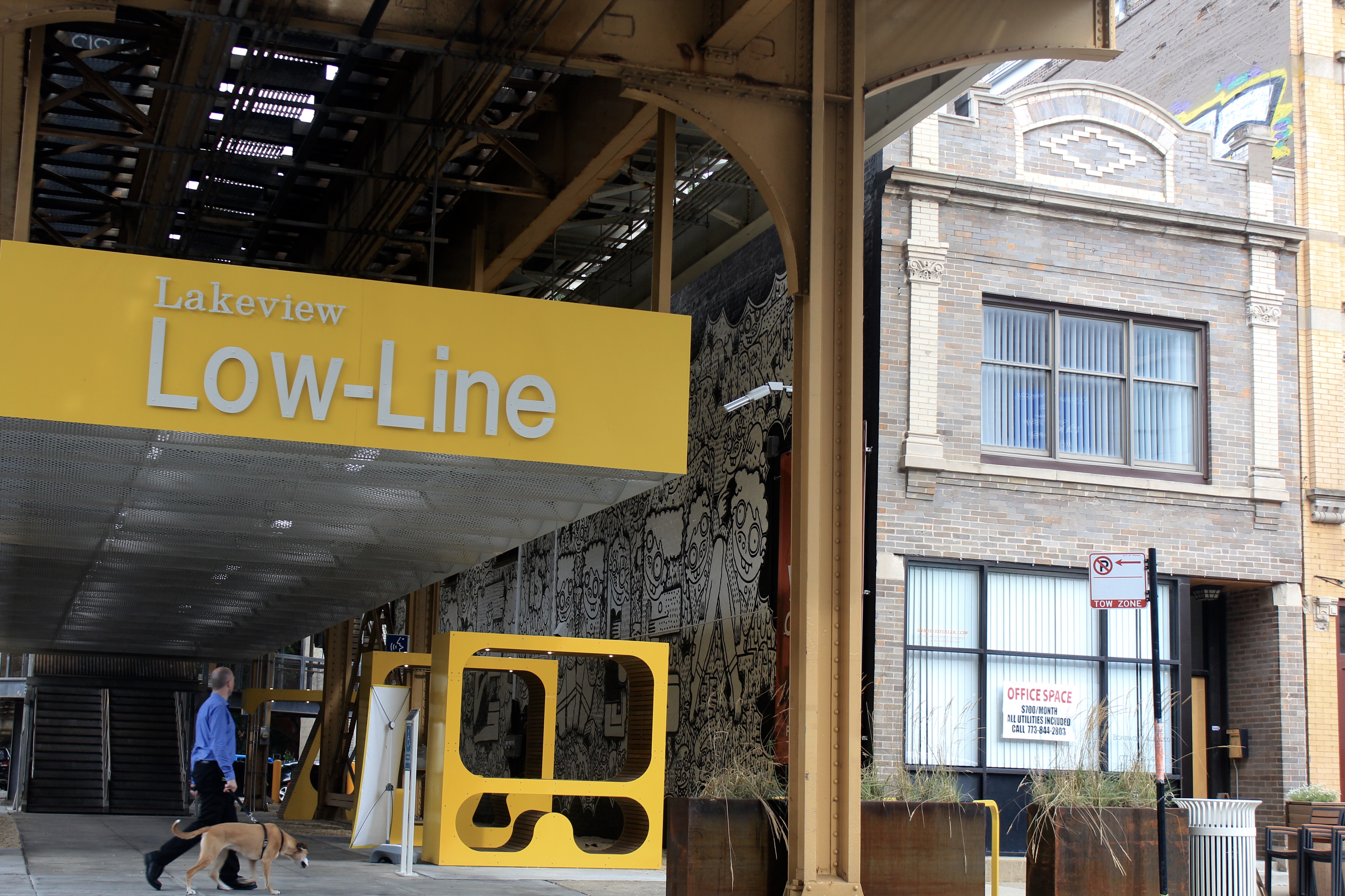

The new Lakeview Low-Line features two ground-level murals at the Paulina Brown Line. The upper-right corner shows where JC Rivera’s third mural was painted over and then tagged with graffiti (Meredith Melland, 14 East).

The Chicago climate also takes its toll on public art, so artists must be prepared.

“We use either outdoor plywood and then coat it with an outdoor paint,” said Hoffman. “[Or] we’ve been using an HTP plastic and that’s what they make playgrounds out of, so those will outlive us,” said Hoffman.

One way to avoid removal is to engage a community while making long-lasting projects, according to Hoffman.

“Most of the time when we put up a piece, the community takes care of the piece, works on it, maintains it, so that gives a really cool sense of ownership,” said Hoffman.

He hopes to continue that sense of involvement with the “You Are Beautiful” Project’s shiny new space in Avondale, which is part-gallery, part-studio and part-workshop space.

“We can have events and talks and workshops and all sorts of different things where we’re creating and we’re helping other people create,” said Hoffman.

Pohlad’s favorite murals also include the historic “Wall of Respect” mural that used to be up in the South Side and some geometric murals along Kedzie. In addition to JC Rivera, Dammalage is a fan of Gamaliel Ramirez and his depictions of Puerto Rican landscapes and communities. The variety of art, the locations and the fleeting nature of murals provides a chase for avid viewers. Pohlad said that murals are often positive and brightly-colored because they are often trying to support neighborhood people in their day-to-day lives. However, it’s pure public access that makes murals special —- anyone can visit them, take Instagrams in front of them or create their own experiences.

“They’re so beautifully public,” said Pohlad. “That’s their whole point: they’re un-ownable.”

Header photo and map by Meredith Melland, 14 East.

NO COMMENT