On a rainy July evening, associate editor Melody Mercado and I met at the Colectivo Coffee on Broadway. We had been talking about working with students to test their tap water for lead contamination in the spring. Halfway through the summer, we finally found time to meet and plan our water testing project. What we planned that evening is vastly different from what we are concluding with nearly 11 months later.

The City of Chicago offers a free water test for residents to test their water for lead levels. Residents can order the test online to have one mailed to them. They just have to complete the test and schedule a pickup. Our plan was to facilitate this process by ordering the test for students and helping them through it.

We planned on getting students to sign up for our project during the first few weeks of Fall Quarter. We’d work with them throughout the quarter to test their water, receive their tests by January and then publish our results at the end of Winter Quarter. Since it is the end of May and we are finally publishing, that’s clearly not how it worked.

Instead, through many learning curves, hundreds of emails and continuous reevaluation of our plans, we expanded the length of our project to the whole school year, broadened our reach and received a grant from Illinois Humanities and the MacArthur Foundation so we could engage more with our community.

Fall Quarter

When the school year began, we tabled at the Involvement Fair, visited seven environment-focused classrooms and emailed 29 organizations on campus and contacted all journalism professors to increase awareness about our project and encourage students to participate. By week three, over 50 people had signed up for our project and we began ordering water tests.

During this part of our project, MailChimp and mass emails were our main mode of communication with our participants — a distant choice, we learned, for a project designed to build relationships with our community. We saw the consequences of this form of outreach in our response rate — only 11 people told us they had their water test picked up.

So as we neared the end of the quarter, we decided we need to rethink our project, our goals and our tactics. As we began to do this, we learned of a seed-grant opportunity at the People Powered Conference. We applied, workshopped our project at the conference, pitched it to event organizers and ended up receiving a grant to support our work. At the conference, we learned new ways to work with our community — from listening sessions to world cafes, to build relationships with DePaul students — which ultimately formed our new plan.

Winter Break

During Winter Break, we developed a new timeline for the plans we pitched at the conference. This included expanding our team from two to six, holding six listening sessions and one large conversation event, and creating some kind of handout with information and resources at the end.

Winter Quarter

In January, we brought on four new people to our team and did more outreach to encourage students to sign up for our project. We visited three classes, attended the Winter Involvement Fair, emailed over 20 campus influencers (campus leaders from student government association to sororities and fraternities), hung 100 flyers across campus, published a story on our site about our project, and promoted it on Facebook and Instagram. By week four we divided all of our new sign-ups and our old — a total of 96 students and community members — among our six team members. This became what we called our “cohort” and each team member was responsible for helping their participants through the process.

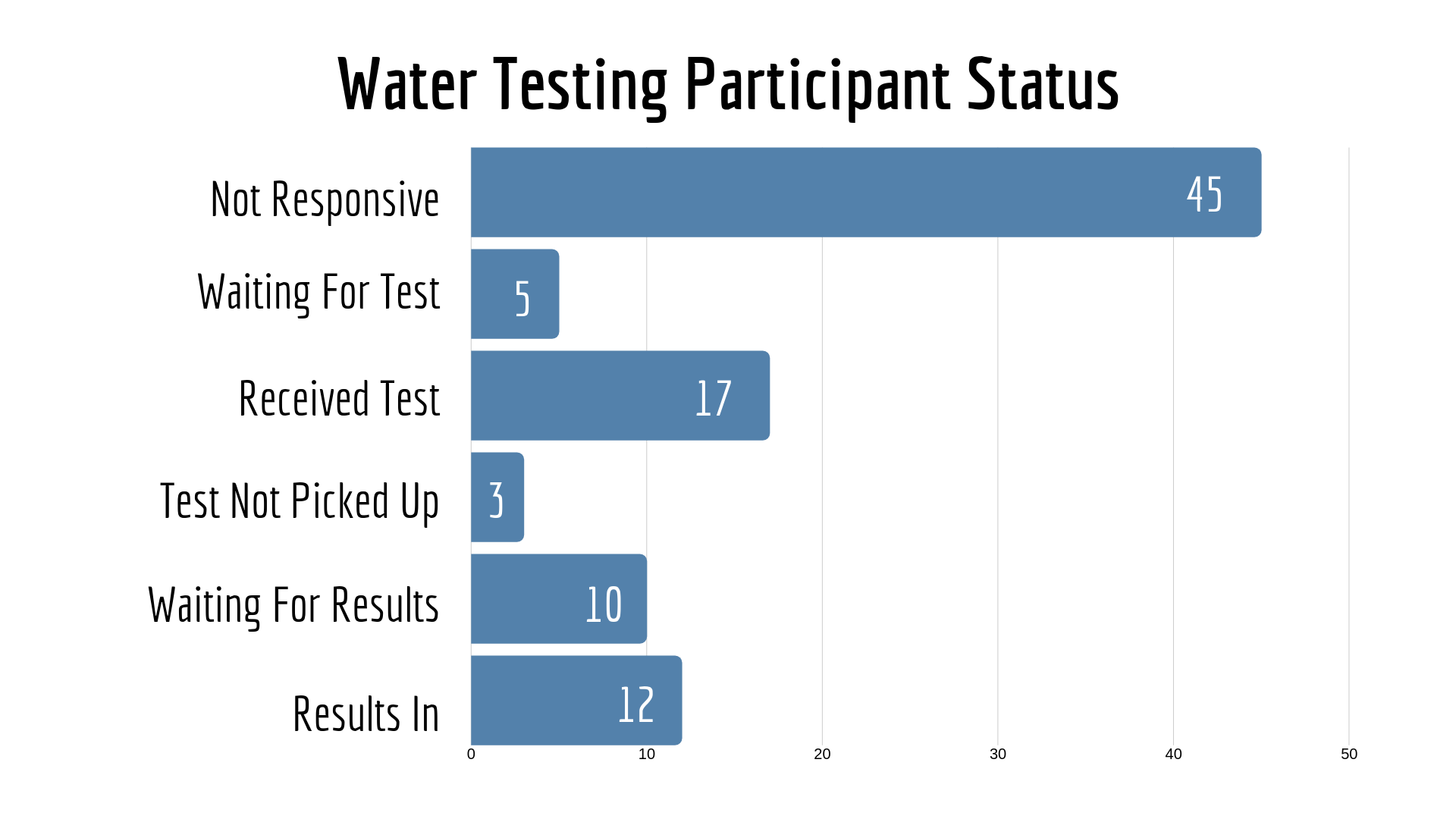

We set a deadline of the beginning of March to have all participants complete their test. However, this is not how it worked out. Even through personal communication, it took awhile to help students through the process. Some eventually made it through the process, while others didn’t. In fact, of 92 participants, 42 stopped responding to us and only 11 have received their results so far. The rest are floating somewhere between waiting for their test and waiting for their results.

Graph: Marissa Nelson, 14 East.

While we waited for participants to submit their water tests, each of us held a listening session with a student in our cohort. In doing so we wanted to learn more about why they joined the project, what they wanted to know, and what other issues/topics were important to them that 14 East wasn’t reporting on. After we completed or listening sessions, we published a story about what we learned.

During the project, we recognized that though much of our project hinged on responses from students and our cohorts getting further on in the water testing process, there was still information we could use to improve our reporting: we knew where 92 students lived. This meant we knew their neighborhood, community area and ward.

So, as the mayoral and aldermanic elections approached, we used this information to cater our reporting to the areas we knew DePaul students live in. In February we published a round-up about the aldermen running in the top five wards we knew students reside.

Spring Quarter

The majority of our cohort didn’t finish their water tests before Winter Quarter, so while we began reporting and planning our final event, we also continued to help our participants through the process.

At this point, we began reaching out to public officials, experts and those affected by lead contamination in their water.

Photo: Melody Mercado, 14 East.

We also used data already available from the city about results from tests already completed around the city to identify hotspot areas with high lead levels. While we couldn’t pinpoint the exact addresses, we were able to narrow the information down to the block the residents live on. So we handed out a letter about our project to 60 homes in 2 neighborhoods, hoping someone would contact us.

Someone did.

Paul Jones, an Irving Park resident, responded in mid April and we set up a time to meet him and his family at their house.

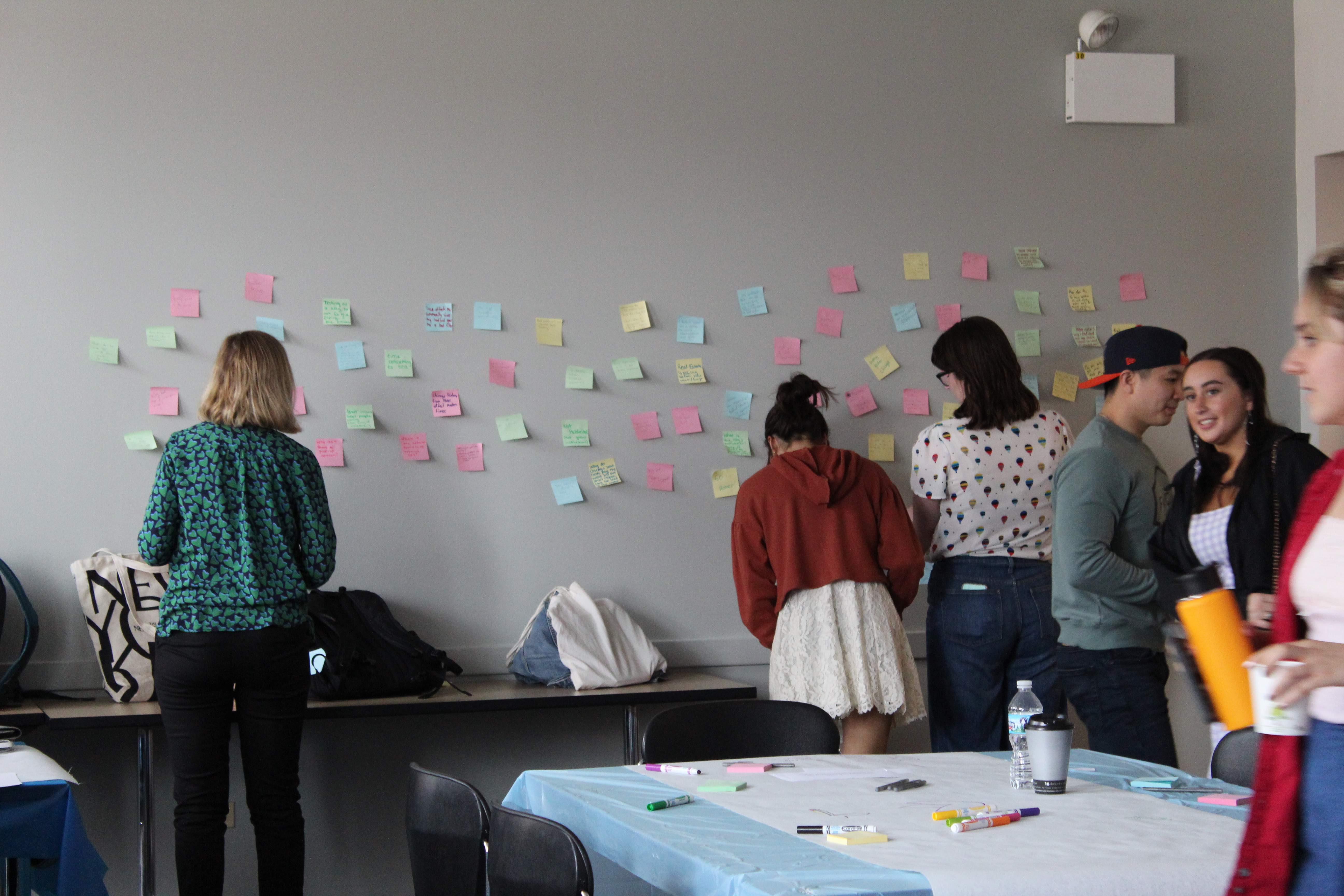

Meanwhile we continued to plan our final event, Water Health and Safety: A Community Conversation. The event, which we held on May 18, was designed to bring together people involved in the issue to talk about some of our reporting and where we go from here.

We invited the aldermen of the wards we know students live in, all of our participants, DePaul students who might have an interest in our project (from journalism to environmental studies and public policy), reporters who have covered lead, city residents and community organizers. However, of the 17 people who came, only three were not DePaul students.

Photo: Melody Mercado, 14 East.

Once we finished our community conversation, we began finishing up our reporting — basing some of it off of what we learned from the world cafe, a structured conversation in which groups of people discuss a topic and periodically change tables to share knowledge.

As we approach the final weeks of the quarter, we have a few more parts of our formal project left that we plan to complete, and many ideas for the months to come. A major theme we noticed throughout our reporting is that DePaul students are largely unaware that their water at home could have unsafe levels of lead in it, and they don’t know the history of lead in Chicago. So we plan on thinking creatively about how we distribute our reporting so that those who need the information, receive it.

However, we also noticed that there are still a lot more questions (both that we have as a staff and that our students have vocalized to us). So we plan on continuing our reporting as the story of lead in Chicago continues to unfold.

If you would like to join us as we continue our reporting — either by testing your water at home or participating in another way — please fill out the form below.

Melody Mercado, Marissa Nelson, Francesca Mathewes, Chris Silber, Hector Cervantes, and Elle Lynch contributed reporting.

This investigation was made possible by funding through the Illinois Humanities, News Integrity Initiative and the MacArthur Foundation.

Header image by Melody Mercado, 14 East.

Invest in Student-Led Community Journalism on Giving News Day – Fourteen East

4 December

[…] year, we worked with 92 DePaul students to test their tap water for unsafe lead levels, publishing a 12-story issue based on what we […]