Editor’s Note: This story details CTA riders’ experiences of sexual harassment. To learn how to report sexual harassment on the CTA, and what will happen when you do, view and save 14 East’s guide to your home screen.

Passengers seldom tell transit personnel, CTA shows minimal effort to prevent harassment

Brianna Saldana, 17, was working on calculus homework while she rode the bus home from work, like she does every Friday night. However, on this October evening Saldana felt a sense of danger — stronger than she had experienced in the past — when a man sexually harassed her for most of her hour-long bus ride.

Saldana works at a large retail chain downtown and takes the bus home south past the Roosevelt CTA stop instead of the ‘L’ out of the Loop. She feels safer this way. It was late, after 10 p.m., so the bus was relatively empty with only about 10 people.

A man eating a Subway sandwich got onto the bus three stops after Saldana. He wore a lime green sweater and appeared to be older than her, maybe in his late 20s or early 30s. The man slid into the seat directly behind her and grabbed Saldana’s left shoulder, pulling her backward. Surprised, Saldana turned to look at him.

“I’m just trying to talk to you,” he said to Saldana. She could smell the sandwich in his breath.

“I just brushed it off at first as if it’s just some crazy dude,” Saldana said. Twenty minutes went by, the bus was now full and the man hadn’t done anything else, so Saldana relaxed. She thought he would leave her alone.

Suddenly, the man pulled Saldana’s hair and grabbed her head. She remembers feeling like she was in danger, and she didn’t know what to do. No one on the bus did anything to intervene. When Saldana told the bus driver, he told her to move to a different seat.

With 30 minutes left until her stop, Saldana moved. The man moved, too, and tried to talk to her.

“Why are you ignoring me?” he asked. “Why don’t you want to get to know me? What’s your phone number?”

Saldana kept her eyes glued to her phone with her headphones in, pretending she couldn’t hear him. She scrolled through Instagram, trying to look busy.

“I was sitting toward the back exit and whenever someone got off he would make sure to check that I was still there,” Saldana said. “At that point I was paranoid that he was just waiting for me to get off. I was texting my friend frantically like, ‘What do I do, what do I do?’”

Initially Saldana’s friend, Liliana Villa, thought this was just another guy cat calling her friend. However, as Saldana continued to text her, she realized this was more than the typical sexual harassment Villa and Saldana experience.

“I remember the feeling of my heart sinking and anger filling my throat,” Villa said in an email. “I asked if she had her pepper spray on her, or if she asked for help from the CTA driver. All my mind was focused on was just ensuring that she was okay.”

Ten stops before Saldana’s, the man got off. She didn’t report the incident.

“I know that sometimes you need the exact train car number and all that stuff,” she said. “That’s hard to figure out if you’re reporting it after it happened.”

Saldana is far from alone in her experiences. While exact numbers aren’t clear because sexual violence often goes unreported, studies and personal anecdotes show that sexual harassment on Chicago public transportation is all too common. However, the Chicago Transit Authority’s (CTA) attempts to prevent sexual harassment and enourage passengers to report incidents appear ineffective.

There have been 42 “criminal sexual assaults” and 259 “sex offenses” reported on the CTA since 2015, according to the City of Chicago Data Portal. Seventy-eight of those have resulted in an arrest. Out of the over 1.7 billion passengers who have ridden since then, the total police reports and arrests appear considerably low.

The CTA also tracks complaints of sexual harassment in its customer service database. Between 2015 and 2018, the CTA has record of 334 reports of sexual harassment on CTA property.

Infogram

However, reporting any form of sexual violence is a particularly difficult process for survivors, and as a result of this, few people report incidents. In fact, according to the Rape Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN), only 23 percent of all sexual assaults are reported to police.

“Recognizing how difficult it might be for an individual to file a report in any type of situation, any type of criminal activity, that can be traumatic for a person who is the victim of that,” said Brian Steele, a spokesperson for the CTA, in an email on May 30. “But we always encourage a report to be filed because that’s a documentation of the incident and it helps increase awareness not only of CTA, but also of the Chicago Police Department.”

Map by Marissa Nelson, 14 East.

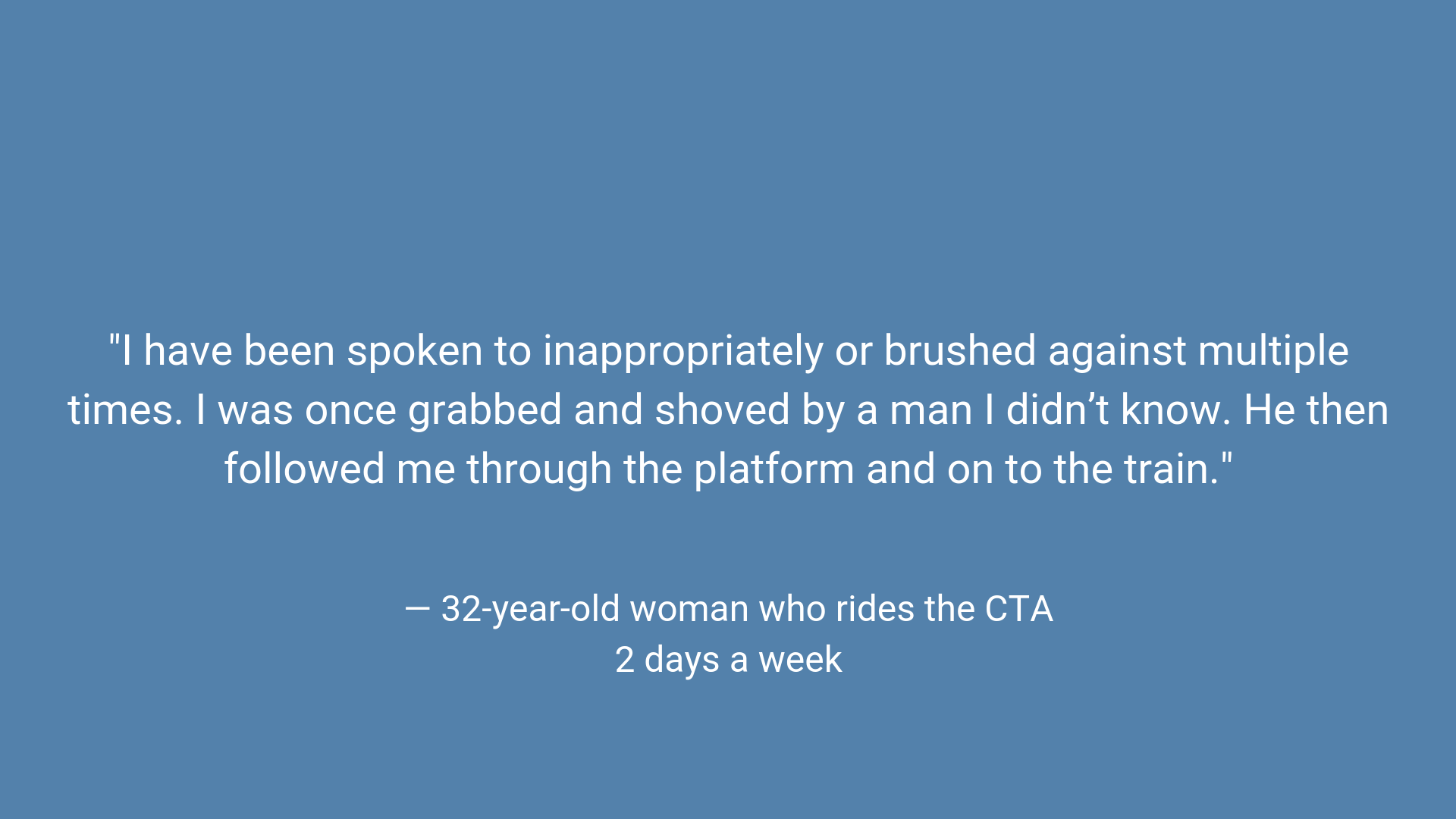

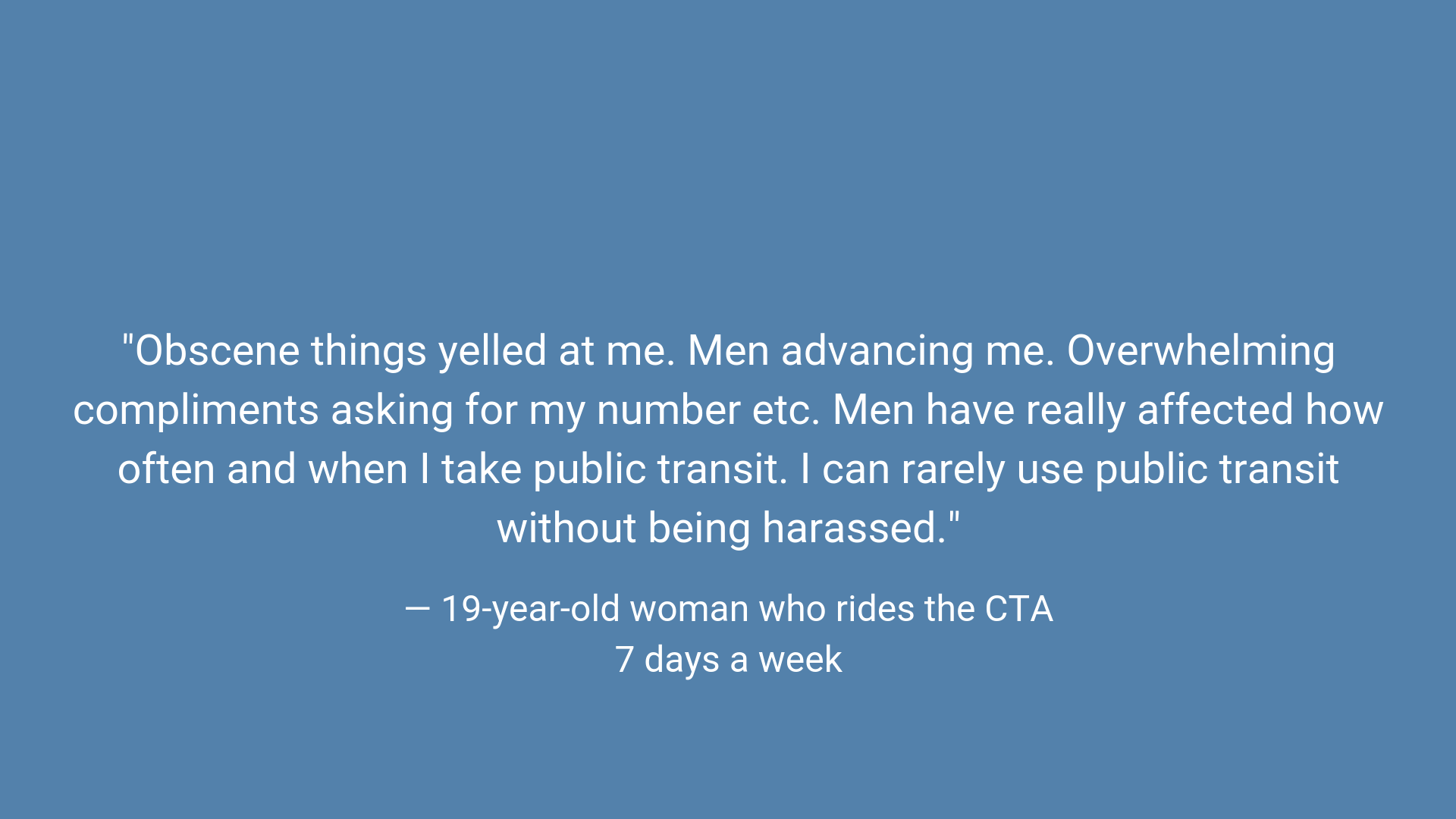

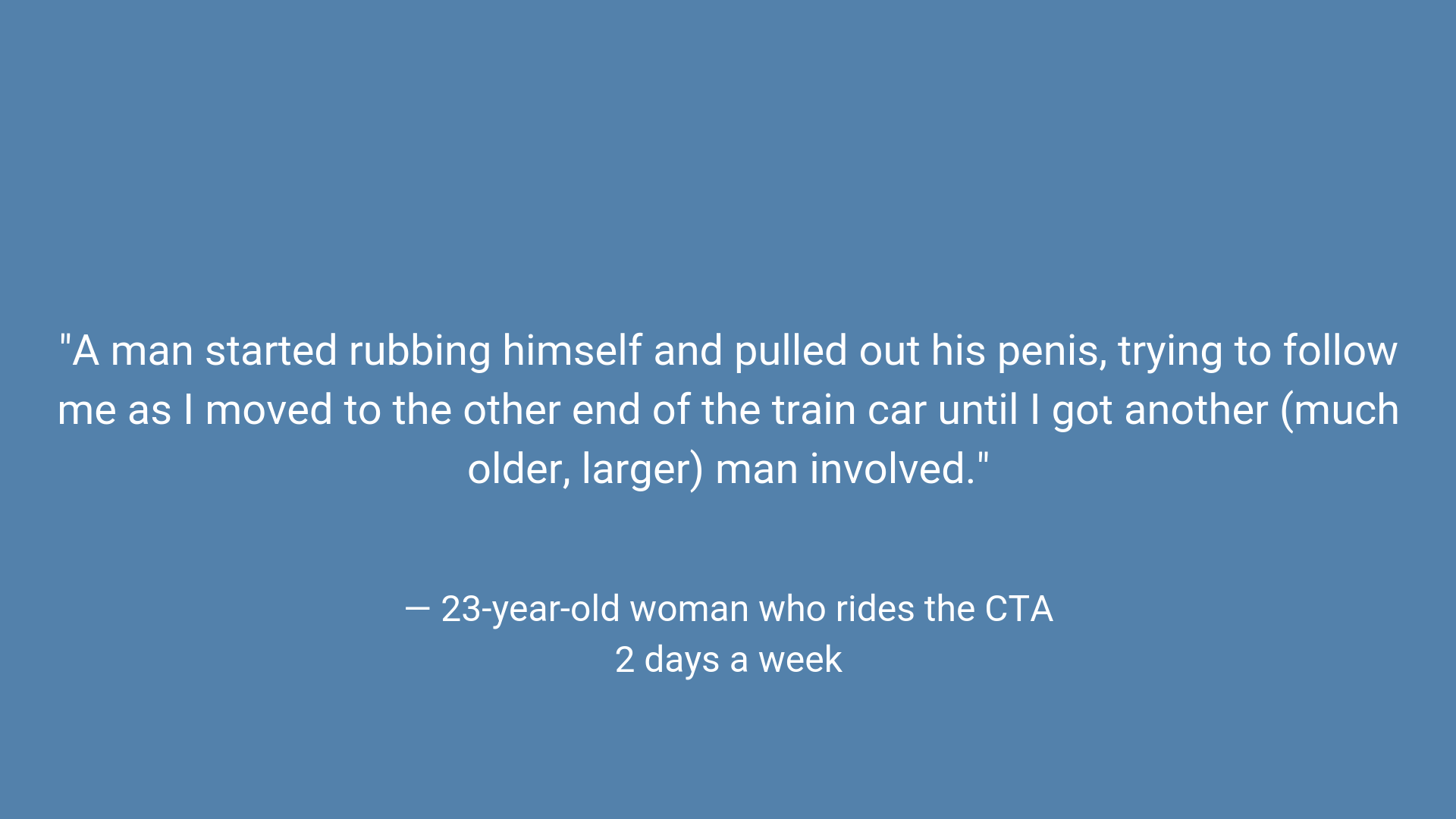

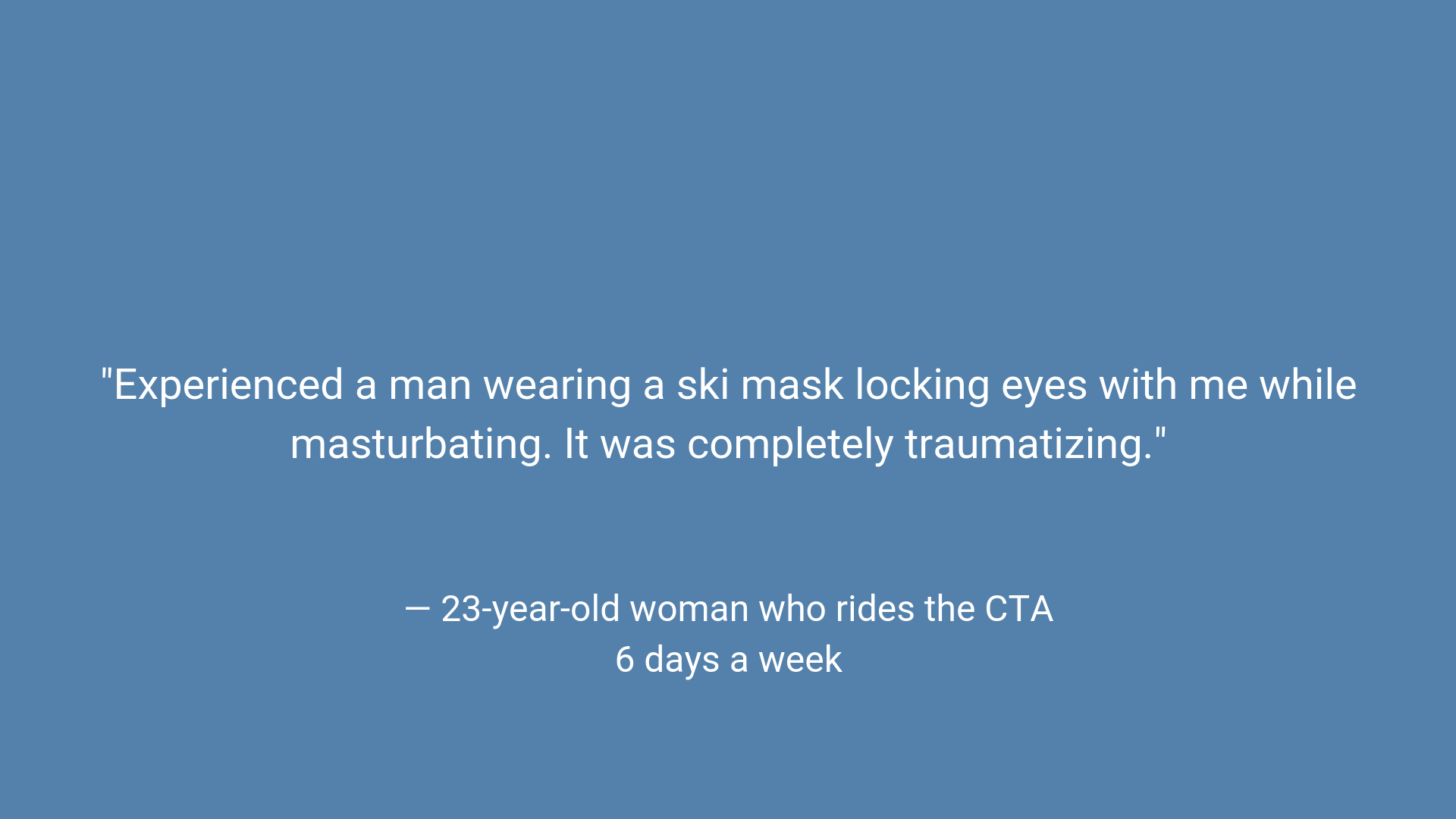

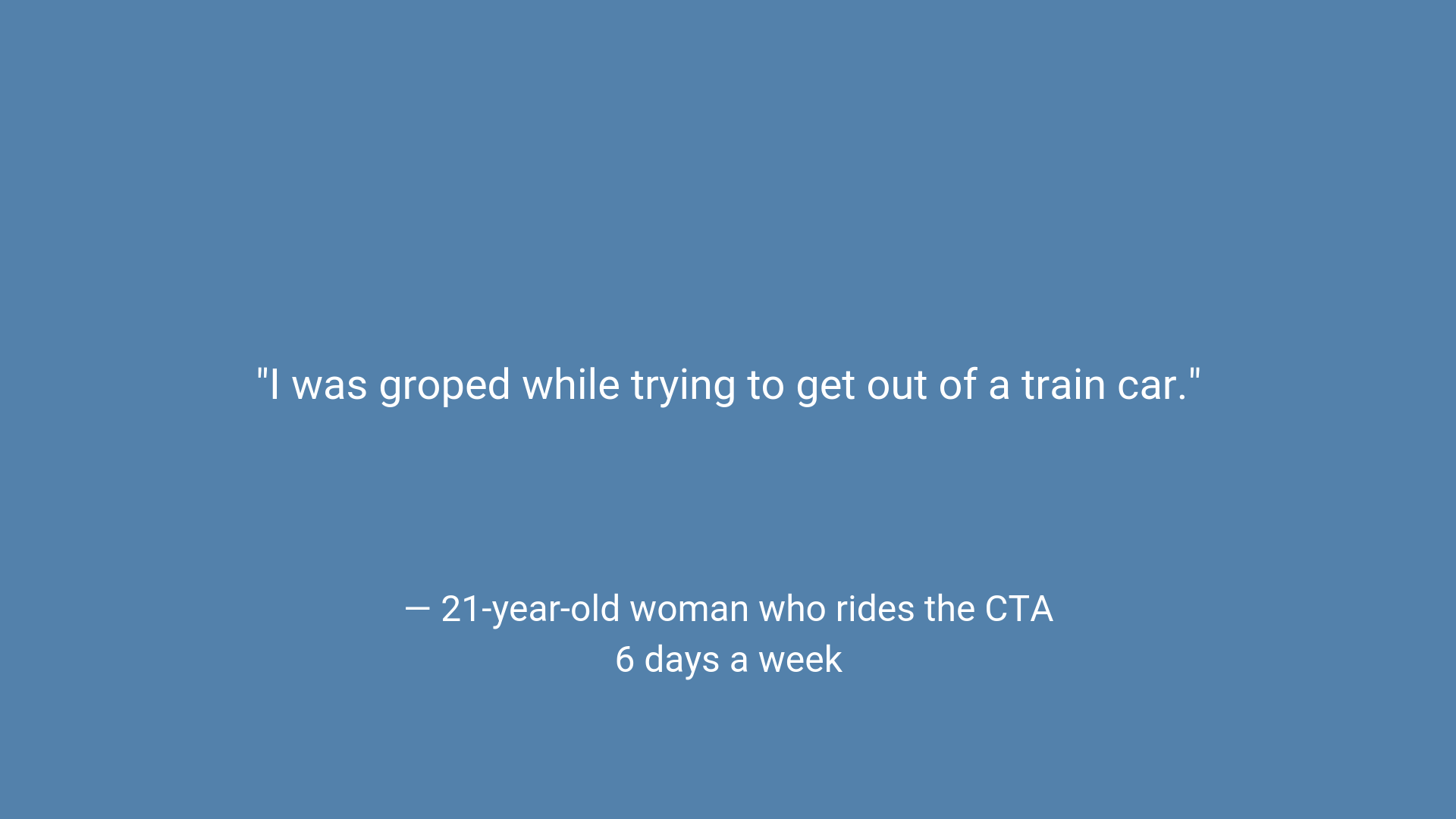

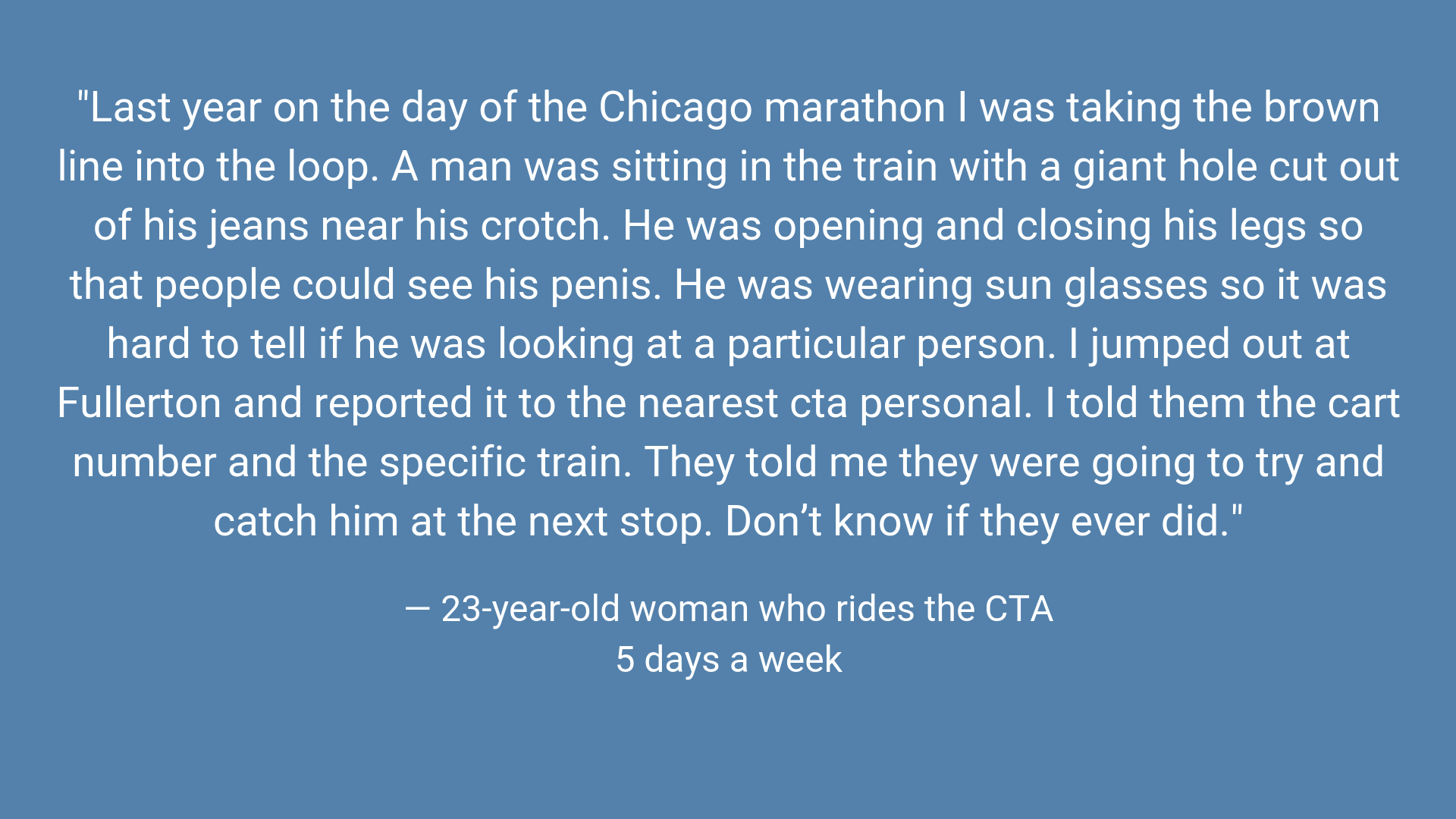

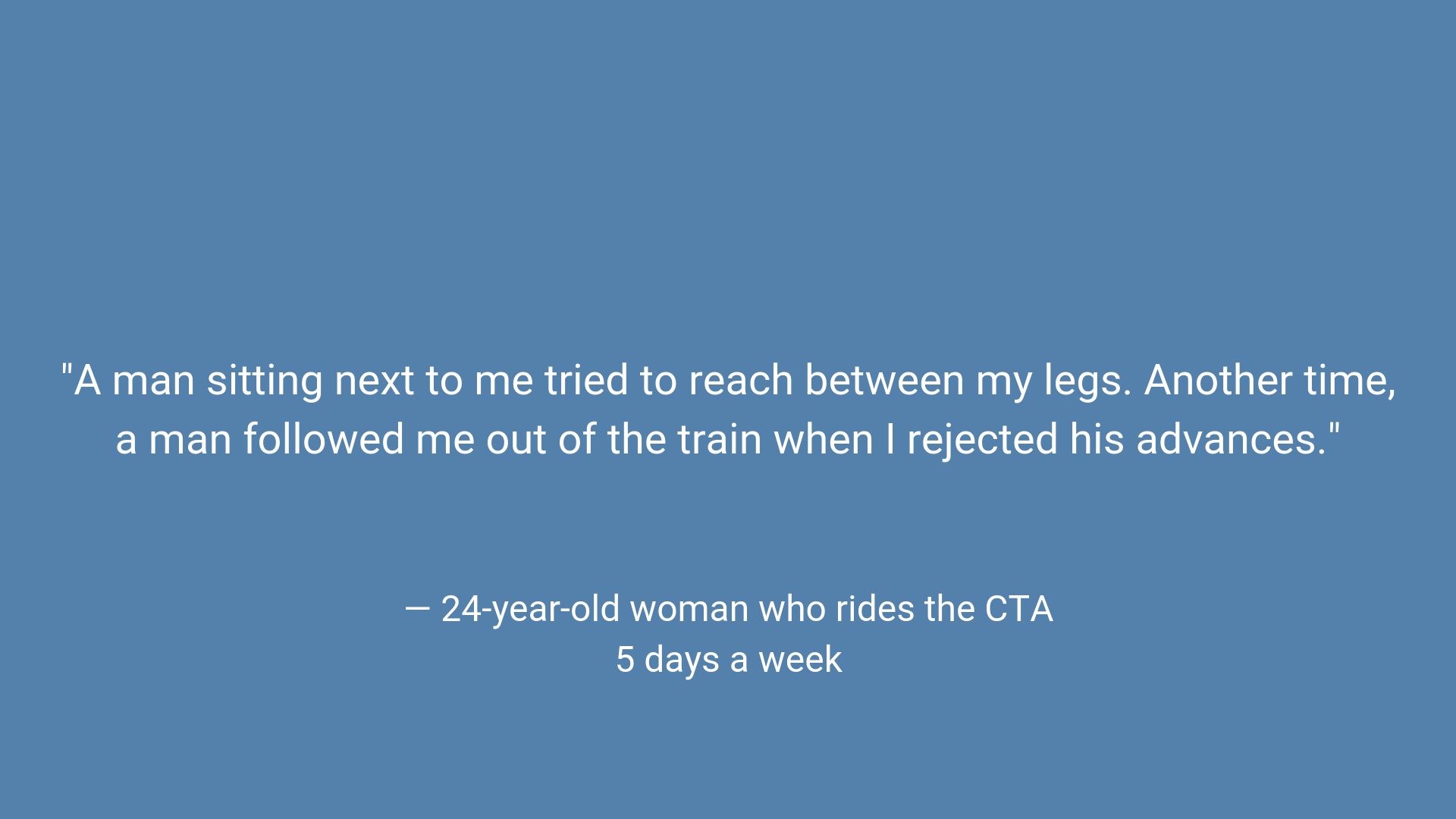

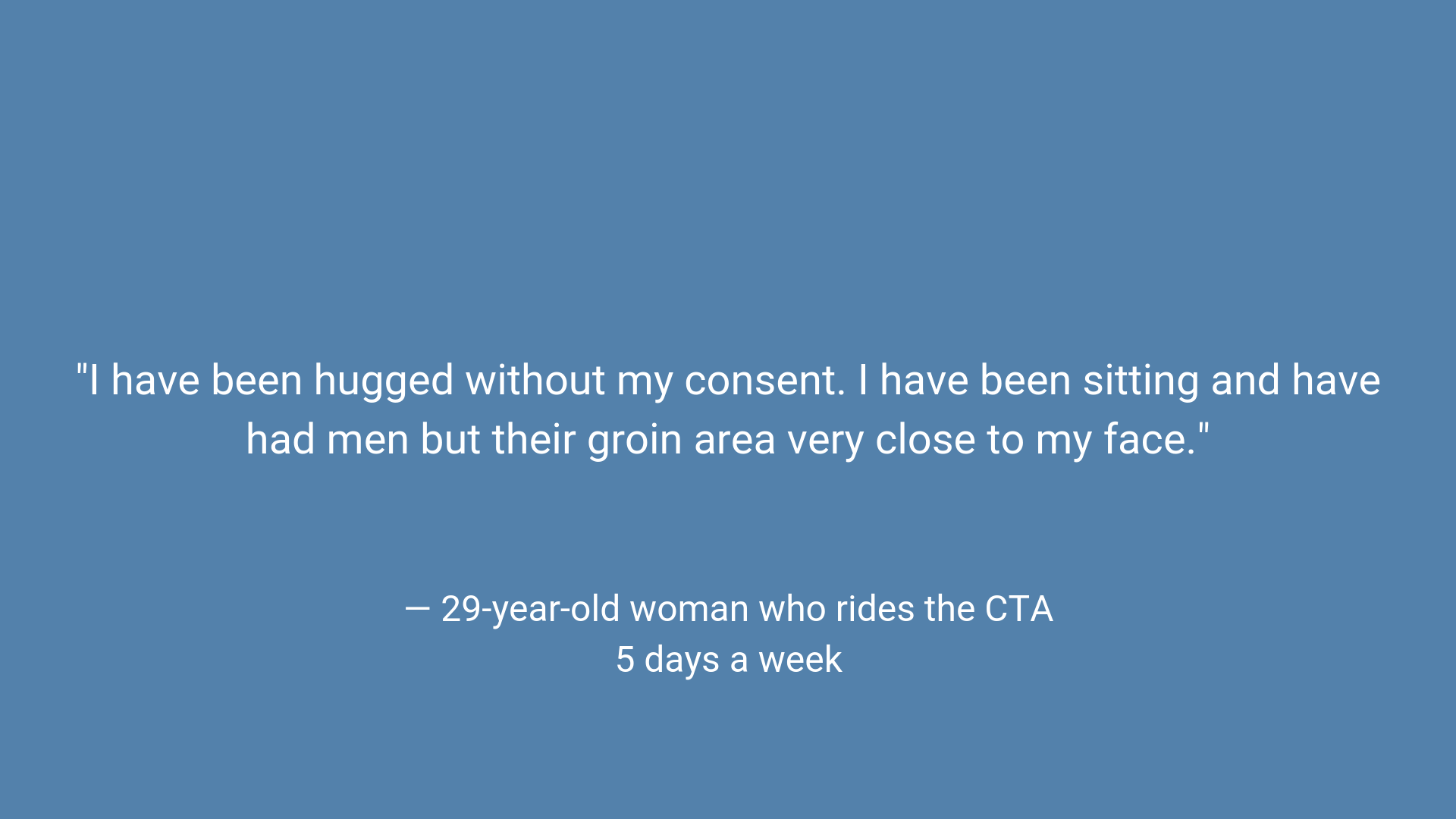

In the fall, 14 East conducted an informal anonymous online survey to gather riders’ experiences, and it appears sexual violence happens far more often on the CTA than data suggests.

From October 13 through November 13, 2018, 14 East distributed the survey in three different ways. 14 East handed out 120 flyers with a link to the survey at the Chicago Women’s March to the Polls, emailed the flyer to 10 Chicago groups and organizations that might be interested in filling it out and distributed it on social media and in our weekly newsletter.

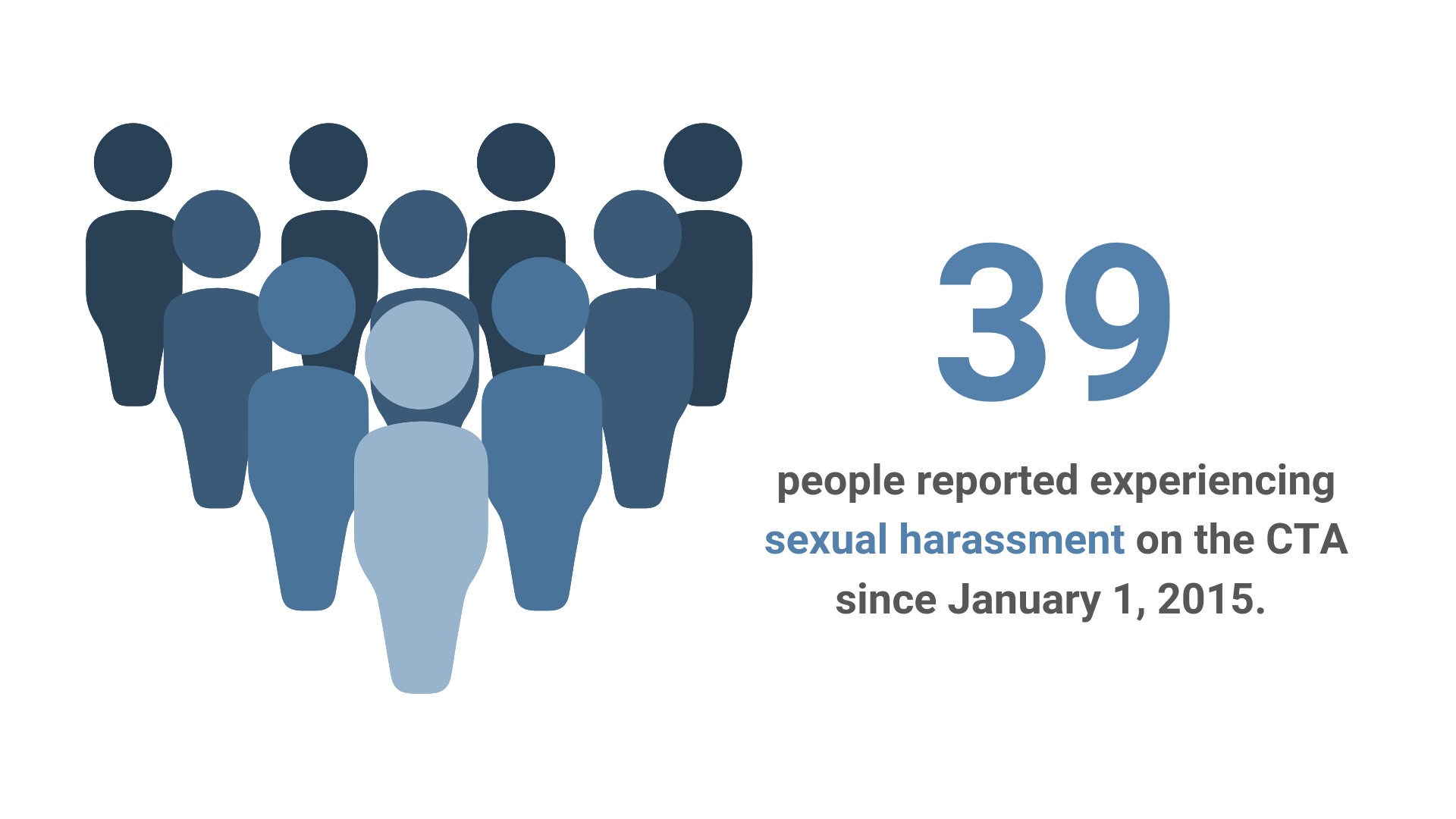

Nearly 130 people responded to the survey, the majority of whom were women. Eighty-two respondents filled out the entire survey. Of those who responded to the full survey, 39 had experienced sexual harassment on the CTA since January 1, 2015. Among the 39 people who had been sexually harassed, 34 said they experienced it more than once. While those numbers aren’t necessarily representative of all CTA riders, they begin to paint a picture of the frequency of sexual harassment that many face daily riding public transportation in the city.

Six of the 34 people who said they had experienced sexual harassment said they told the CTA, and three of those six also filed police reports.

Graphic by Marissa Nelson, 14 East

Other studies have also verified that sexual harassment on public transportation might be more common than some think. A national survey of 2,000 people released in February 2018 found that 17 percent of respondents had experienced sexual harassment on “mass transportation.” When broken down by gender, 26 percent of women and 8 percent of men reported being sexually harassed on mass transit.

Saldana said that she frequently experiences sexual harassment on the CTA. She explained in detail three other times someone had made her feel uncomfortable and unsafe.

Over the summer, when waiting for the bus with her mom, a man told her that she was “so sexy.”

In spring 2018, while waiting at the Pink Line Damen stop for a train going inbound to the Loop, a man told Saldana and her best friend that they had “model bodies” and that they were sexy.

In 2013, when Saldana was in eighth grade, she said a man followed her as she left her train stop. Instead of going home, she waited in a Walgreens near her house until the man left.

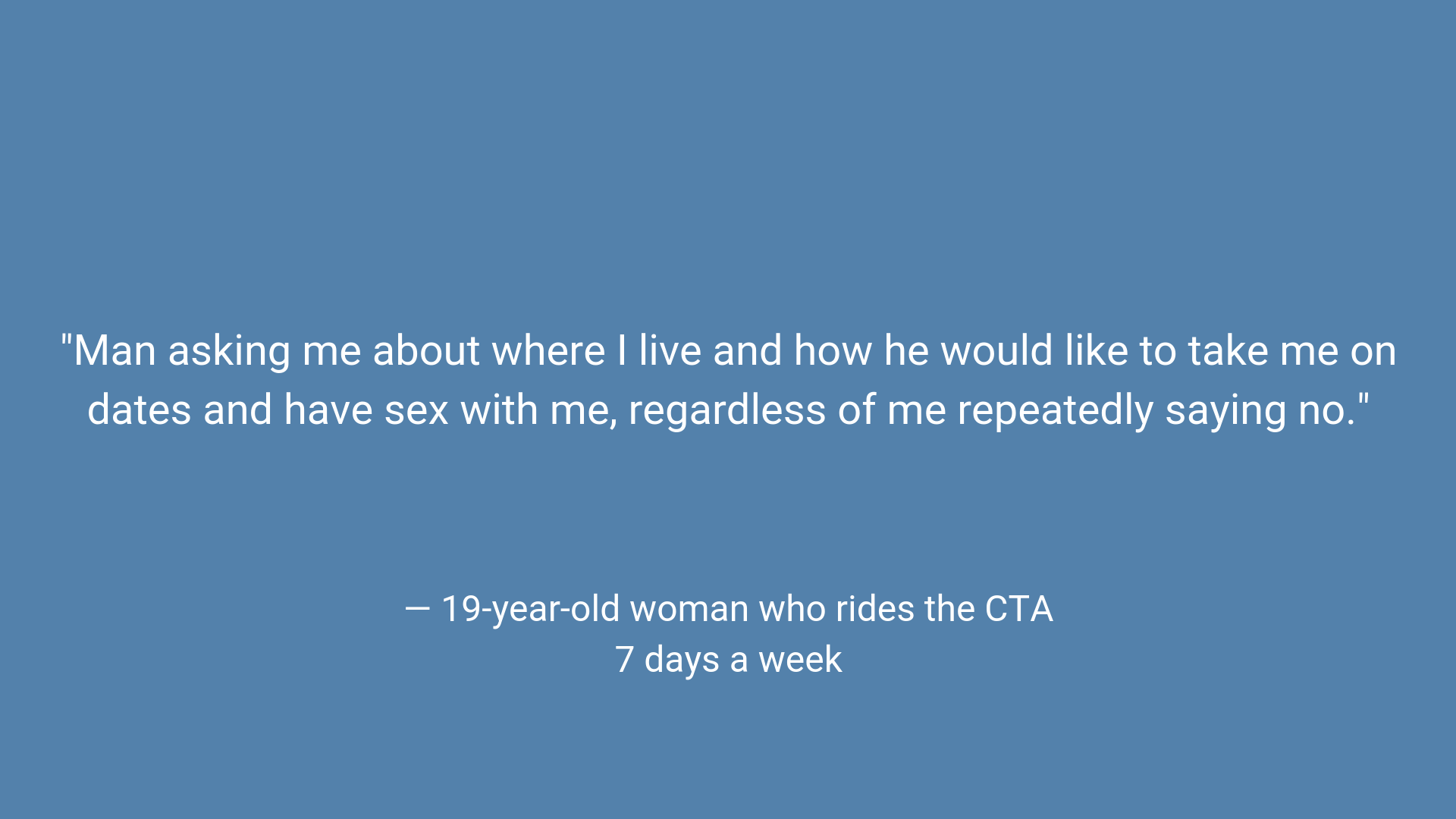

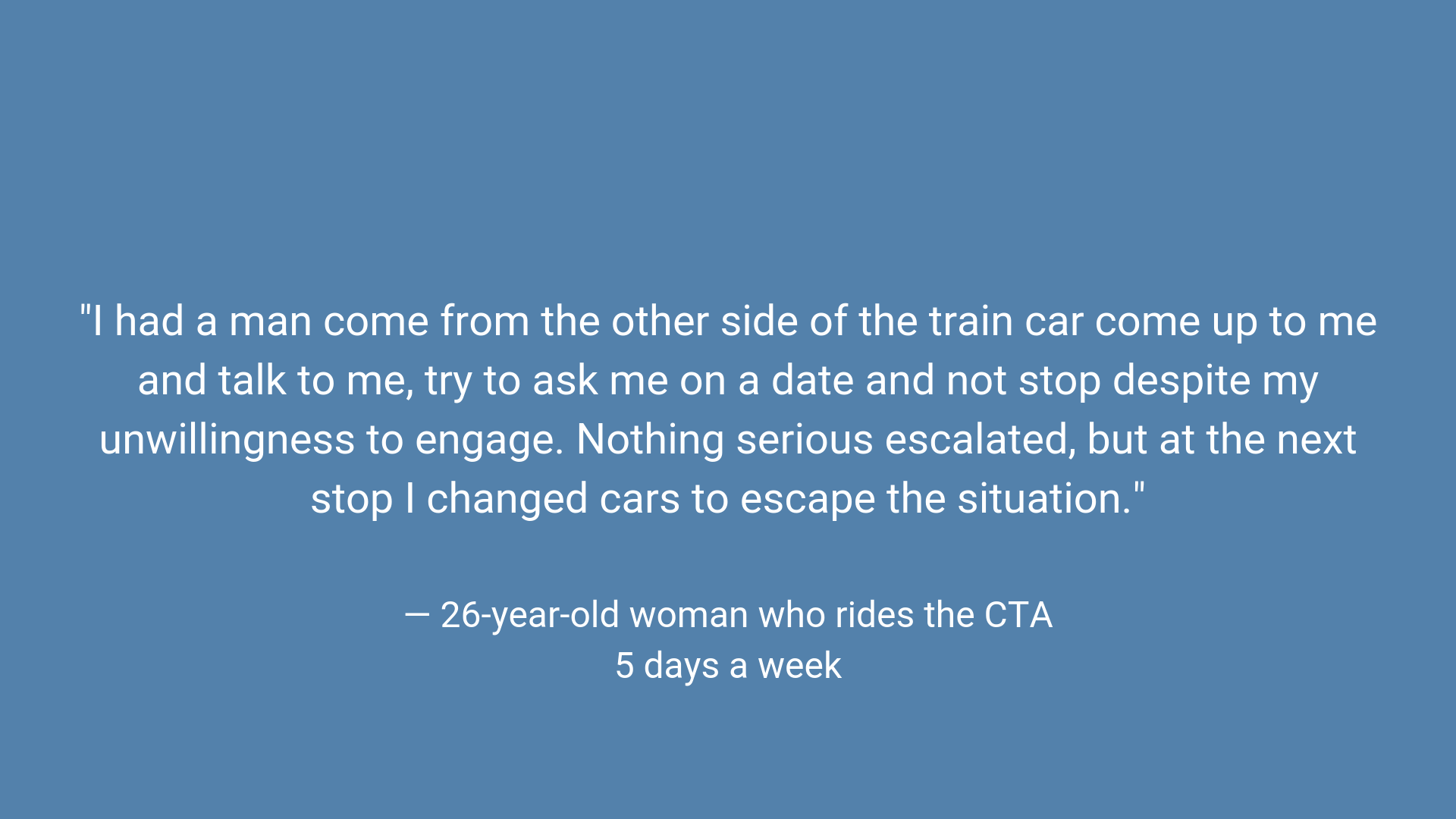

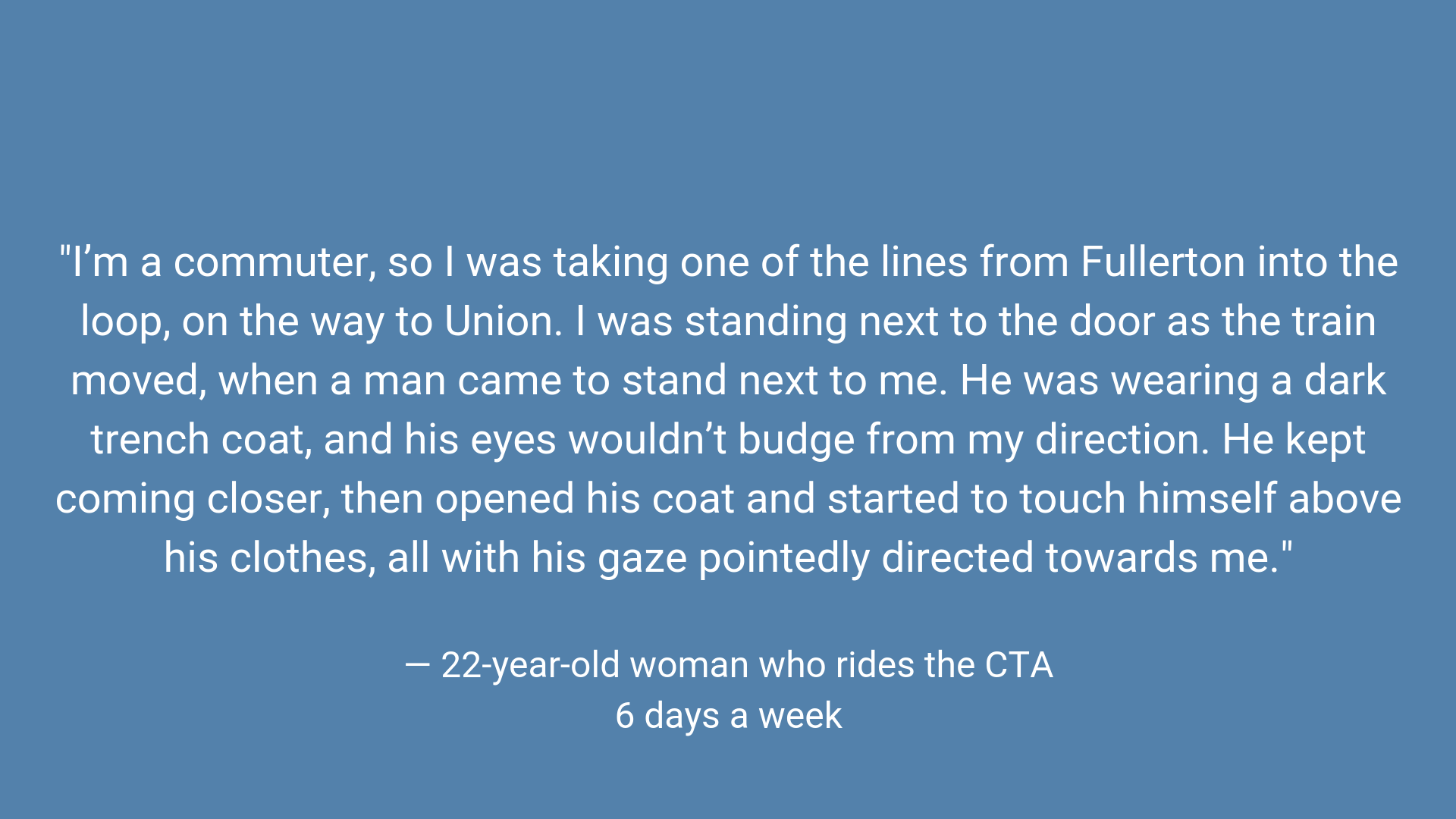

Respondents to 14 East’s survey echo Saldana’s experiences of “cat calls,” “unwanted touching” and “vulgar comments.” A 24-year-old woman wrote that a man sitting next to her on the train “forcibly took pictures between [her] legs.” A 19-year-old woman said that men have put their “groin area very close to [her] face” while she was sitting on the train. A 42-year-old woman reported seeing a man masturbate at her train station and men touch “themselves inappropriately on the train.”

What’s been done to prevent sexual harassment on the CTA?

In August 2014, Kara Crutcher, an Uptown resident who had been sexually harassed on the CTA, tried to address this trend. She started the Courage Campaign, an informal initiative that raised money for anti-sexual harassment advertisements on the CTA. However, CTA’s ad agency, Titan Worldwide, considered the campaign’s advertisements to be “public service announcements” and required that such be posted by the government or a nonprofit organization. The Courage Campaign was neither.

So, Crutcher and others involved with the campaign — roughly 25 people between 2014 and 2015 — gathered stories of sexual harassment on the CTA. Crutcher also began working with Jaime Schmitz at Girl World, a program at Alternatives Inc. that works with 14- to 17-year-old girls to build “self esteem and self advocacy.”

On July 15, 2015, Crutcher and Schmitz spoke at a CTA board meeting, sharing their concerns and stories of sexual harassment. The board members seemed receptive to her message, Crutcher said. The CTA employees that the board referred her to at the end of the meeting, however, did not.

“After the meeting they were trying to explain the protocols they had in place for sexual harassment,” Crutcher said. “Which wasn’t what I was trying to do because, one, I came into this knowing and feeling like they were insufficient and also knowing that there were insufficient ad placements about this issue on the trains and on the buses.”

A few months later the CTA announced its anti-harassment campaign on October 9, 2015, called, “If It’s Unwanted, It’s Harassment.” The campaign built off an earlier “public service campaign,” according to a press release. It included campaign posters with four different messages that were hung up on CTA trains and buses.

Three of the four advertisements from the CTA’s campaign instruct passengers how to report harassment to the CTA. And all of the posters read the title of the campaign — “If it’s unwanted, it’s harassment.” According to Steele, the advertisements are still up on most CTA trains, buses and on digital screens.

“It was not enough in my opinion, and I could definitely be happier with it,” Crutcher said. “I don’t think they were as bold as they could be. I don’t think they were as blunt as they should have been. I don’t mean in terms of being sexually explicit but something like, ‘Hey, did this happen to you — hey, step one try this, step two, try this,’ you know?”

One of the CTA’s poster designs released for its 2015 anti-harassment campaign.

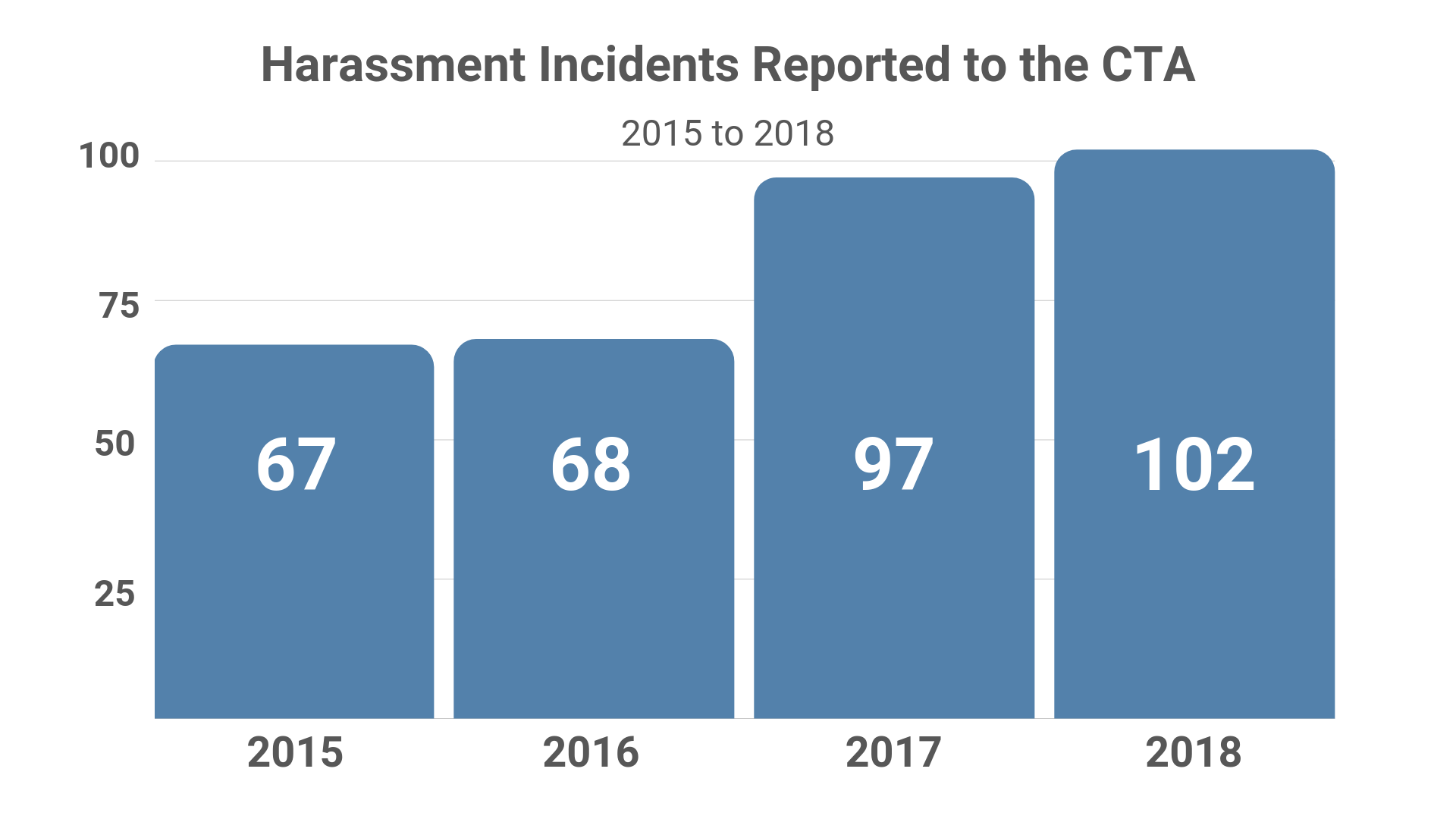

Since the CTA launched the anti-harassment campaign, the transit system has seen a slight increase in reports of harassment. From 2015 to 2016, the CTA received one additional report of harassment, increasing from 67 to 68 reports respectively. The following year the transit system received 97 reports; that’s 29 more than in 2017. And in 2018 — on the heels of the #MeToo Movement — the total number of reports of people experiencing harassment jumped to 102, according to Hosinski.

Graphic by Marissa Nelson, 14 East

In terms of police reports filed, as of 2018, 214 CTA sex crimes have been reported to CPD, according to the City of Chicago Data Portal. That’s a 20 percent increase from the three years prior to the 2015 campaign. Steele said that one of the goals of the campaign was “to encourage those who have experienced harassment to report it.” In that respect, the campaign was successful. However, a 20 percent increase is only 36 more reports than in the three years prior to the campaign.

Reporting Sexual Harassment on the CTA

In the early fall of 2011, Kelly Crook frequently rode the CTA to and from work. One evening during rush hour, while waiting for the outbound Red Line at the Jackson stop, a man complimented her black low-top Converse shoes with white laces and asked to ride the train with her.

“I was so uncomfortable. I didn’t know what to do,” Crook said. “I shook my head and I was like, ‘Okay,’ figuring that once we got on the train I’d be able to distance myself from him.” The man continued talking to Crook for a little over a minute and then stepped closer to her and whispered in her ear, “Do you like bubble gum?”

“As he was saying that he rubbed his penis against my leg,” Crook said. She stepped backward. “I said, ‘You’re making me uncomfortable. I’m sorry, please go away. You’re making me uncomfortable.’ He kind of stood there and I said, ‘When a train comes I am going to get on this car and you are going to get on a different car,’ and then he kind of walked away from that.”

She didn’t report the incident.

“I didn’t think to do it. I was glad it was over and I just wanted to get myself out of that situation. When I got home and told my roommate about it she was like, ‘You should tell somebody,’ and I was like, ‘They’re never going to find that guy, like nothing is ever going to happen if I do anything.’”

Seven years later, Crook’s roommate, Julianna Hincks, still remembers learning about the incident.

“I was not surprised, but I was upset to hear her story,” Hincks said over an email. “I remember thinking that they wouldn’t listen or care or even be able to do anything for her. I do wish there was a sympathetic, understanding CTA contact for situations like this.”

This hesitancy to report harassment — and uncertainty as to how the CTA will handle reports — is not uncommon. Among those who responded to 14 East’s survey, 32 of the 39 people who had been sexually harassed on the CTA did not report it. In fact, 73 people said that they don’t know how to report sexual harassment.

According to the CTA’s website and the anti-harassment campaign posters, a person who is harassed (or witnesses harassment) has a few options for reporting. If in immediate danger the CTA says a passenger should call 911 or contact transit system personnel.

“All CTA employees undergo anti-harassment training, and field personnel — train operators and station staff — are trained to handle all reports of this nature and ensure CPD is contacted,” Steele said in an email on November 14, 2018.

If a passenger tells CTA personnel that they have been sexually harassed, the employee will contact the transit system’s control center, which will then notify the Chicago Police Department. CPD will then try to track down the offender by meeting them at the next train or bus stop, according to Steele.

Otherwise a passenger can report the incident to CTA Customer Service by calling 1-888-968-7282. In this case the complaint will be recorded internally and shared with the Chicago Police Department.

“CTA works very closely with CPD on all law-enforcement matters, including daily interface with its Public Transportation Unit, a unit of officers dedicated to the CTA,” said Steele in an email on June 11. “Among the CPD strategies are deployment of both uniformed and plainclothes officers, surveillance missions based on developing trends in activity, and is often based on incidents reported directly to police, to CTA Customer Service or by personnel to management.”

To learn how to report sexual harassment on the CTA, and what will happen when you do, view and save 14 East’s guide to your home screen.

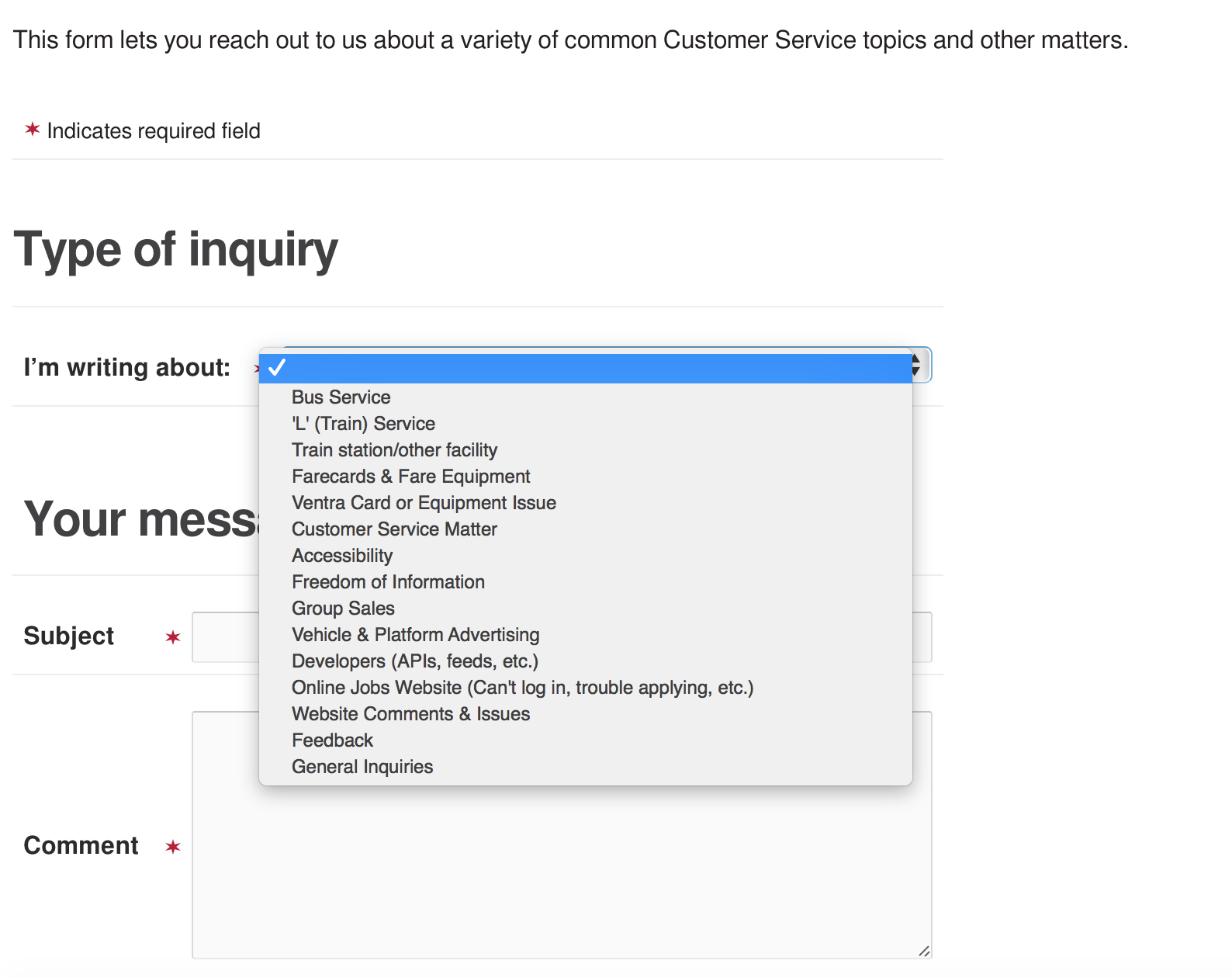

CTA’s website also offers passengers the option to report an incident online. However, the form is a default “feedback form” created for a variety of inquiries ranging from platform advertising and group sales to accessibility and fare card information. There is no specific option to report sexual harassment.

A screenshot of the feedback form the CTA tells passengers to use to report sexual harassment.

After the CTA receives information about sexual violence — or any crime — the information is given to CPD. If the passenger chooses not to file a police report, Steele said the information is still distributed to CTA employees so they can look out for the offender.

Steele also noted the CTA’s security cameras as a way to prevent would-be sexual harassment — according to the CTA’s website the transit system has over 32,000 cameras on its property. However, Dr. P.S. Sriraj, the director of the Urban Transportation Center at the University of Illinois at Chicago, said that having cameras isn’t always an effective prevention method.

“There’s going to be instances where people do not necessarily care whether they are being caught on camera or not,” said Dr. Sriraj. “So all these cameras, technically they help in deterring criminals but they don’t outright prevent crime from happening.”

Dr. Sriraj said that crime and harassment on public transportation, including on the CTA, isn’t a “one solution problem.” Instead, it will take multiple measures to solve. He mentioned more security cameras, increased uniformed personnel, better lighting and signs that “explicitly” inform passengers on what is and isn’t acceptable behavior and how to report uncomfortable situations and find help.

Even with the security cameras on the CTA, though, passengers have a limited amount of time to retrieve the footage. The CTA won’t release the amount of time recording is saved for “law enforcement reasons.” However it appears to be a relatively short period of time.

“It doesn’t last forever and that’s where we really encourage people to report things sooner rather than later,” Steele said. “Even if a few hours or even a day elapses, still there’s time to be able to contact us. Our video system is like any video recording system, it will override itself after a certain period of time.”

Steele said that the CTA is always open to new ideas for prevention.

Looking back, Villa, who received Saldana’s texts while she was being harassed, remembers feeling stunned. She said she knows sexual harassment is common, but it’s still shocking when it happens.

“It is even more shocking when it hits close to home,” Villa said in an email. “Almost every time Bri and I go out some guy has to whistle or holler at us. Even on the CTA, there have been times where guys are just looking at us like we’re a piece of meat (we usually then move seats).”

If Saldana sees the man who harassed her on the bus again, she said she would be “very anxious and nervous” and she’d keep her distance from him. She doesn’t think the CTA would be helpful and she’s not sure what else she could do.

“I mean like I usually tell people to leave me alone,” Saldana said. “I’ll give them dirty looks. I don’t know what I can do. It’s not like I can hit them or anything. I don’t know.”

For more information on what to do if you experience or witness sexual harassment, please read and save 14 East’s guide on what you can do.

If you’ve experienced sexual violence and would like support, you can call the RAINN hotline at 1-800-656-4673 or the National Domestic Violence hotline at 1-800-799-7233 for help.

If you have experienced sexual violence on public transportation and feel comfortable doing so, please tell us about it in the form below.

Header image by Natalie Wade, 14 East.

Slidehow and infographic by Marissa Nelson, 14 East.

NO COMMENT