Contributor H.C Stephens – a current College of Computing and Digital Media (CDM) – Digital Communications Media Arts (DCMA) graduate student – breaks down the what’s, when’s and how’s of Section 230, as the decades-old policy that shelters social media behemoths faces continued stress following the blowback of the insurrection in our nation’s capital. This article is the first in a series on emerging technology and design.

On January 6, an armed mob of insurrectionists, in support of former President Donald Trump, stormed the nation’s Capitol. The events resulted in five deaths, including fatal injuries sustained by Capitol Police Officer Brian D. Sicknick — as of Wednesday , two additional officers have taken their own lives since the riots. During the violent chaos, the Confederate flag publicly made its way into the halls of Congress for the first time in the nation’s history.

The group’s actions mark the only successful infiltration of the nation’s Capitol since British troops stormed what was then called Washington City as part of the Chesapeake Campaign during the War of 1812— the redcoats left the White House, Congress and other government buildings in flames.

While geographic and class differences separated many of the extremists, one thing they shared was a connection to controversial message boards online.

For over a decade, members of what we now call “alternative facts” groups have disseminated their content and connected with like-minded individuals through some of the largest internet platforms in existence, such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube. Recently, outposts like forum site 8chan (4chan’s more perverted kid brother imageboard discussion site) and the emergent Parler have drawn radicals into their corners by providing unapologetic “free speech” zones.

Increasingly, the affordances and protections granted to social media networks have allowed a wide array of communities to occupy the same platforms online — where they are difficult to moderate and police.

Due to the current legal protections in Section 230, the substantive piece of legislation that governs internet service providers (ISPs) and digital intermediaries, these platforms successfully evade the responsibilities that other media and telecommunication companies are held to. This law grants them immunity from prosecution related to their site moderation or any responsibility of governing users.

SECTION 230: The Over Under

In 1996, Congress Passed the Communications Decency Act, which made it punishable by law to distribute “indecent or obscene” materials to anyone under the age of 18 online. Essentially, it prevents minors from being the recipient of pornographic materials. Those who knowingly break the law face steep fines with the possibility of imprisonment.

On face, the core legislation is simple. However, before its passing, a bipartisan amendment was added to the original act providing “safe harbor” for ISPs and intermediaries. The additional clause extended protections to shield ISPs from prosecution so long as they merely provided access to the internet or conveyed information. As such, providers would not be held accountable for the content circulated by their users.

This move aligned the protections of an ISP with legacy telecommunication providers rather than traditional publishers—with some minor exceptions, like intellectual property infringement– we see you, Napster, miss you Limewire.

First, providers cannot be held liable for the speech of their users. In other words, hosts are viewed more like distributors rather than publishers, which makes sense.

To quickly walk you through this: if two individuals plan a murder via telephone, Southern Bell, Ameritech, AT&T, or any other provider cannot be held accountable in a court of law for “facilitating the crime” because of “safe harbor” protections. Whereas, in the case of legacy news media, network television, radio programming, and the like, media publishers can be prosecuted in a court of law for defamation, violation of privacy, negligence and a variety of other claims.

Less than a year after its passing, The Communications Decency Act was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. While judges took issue with portions of the bill, the amendment containing the “safe-harbor” clause was retained. Today we refer to this legislation as Section 230.

The law extends two key protections for ISPs and other intermediaries, including social media companies. First, providers cannot be held liable for the speech of their users. In other words, hosts are viewed more like distributors rather than publishers. Which makes sense, with regard to the examples previously listed.

Here’s where things get interesting — the second piece of the law says that if operators choose to moderate the content of their sites, they will not lose the “safe harbor” protections designated to them.

This means they can amend, curate, promote, sculpt and shape the information exchanged on their platforms free from prosecution — think algorithms.

It’s important to note that this legislation was penned almost a full decade before the rise and peak of Web 2.0 — the virtual renaissance of the post-dotcom era that champions participatory culture that social media enables. Framers of the amendment could never imagine the reality that digital platforming would soon create online.

For years, social media providers allowed the inflammatory messages perpetrated by Trump to go viral as a result of the shelter provided through Section 230. Do these corporations have an obligation to silence problem users? How do they determine and implement their rules, guidelines, and community standards?

Origins of Regulatory Needs

Compared to other technologies, the Internet remains a comparatively untouched legal landscape in the United States. Free to all sizes and shapes, where many web hosts rally behind the ideals of democratization and free speech. As such, social media providers are tasked with demarcating and dispensing decorum.

Because the internet has become positively overrun with interests, communications scholar Tarleton Gillespie argues in 2018’s Custodians of the Internet that policing is what social media platforms provide. “Though part of the web, social media platforms promise to rise above it, by offering a better experience of all this information and sociality: curated, organized, archived, and moderated,” writes Gillespie.

This becomes problematic because social media platforms have abundantly concentrated a vast swath of perspectives, opinions and interests, rendering it impossible to control. Furthermore, providers are reluctant to reveal what level of influence they exert on a user’s experience.

With regard to moderation, Gillespie says, “social media platforms are vocal about how much content they make available, but quiet about how much they remove … sites also emphasize that they are merely hosting all this content, while playing down the ways in which they intervene.”

The procedures these companies follow in determining their “rules and guidelines” as well as “community standards” remains one of the most controversial issues surrounding the subject. The biggest players in the game claim to have never set out to police the world. Therefore, they accept the role slowly and exercise different approaches to setting policy.

Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey told WIRED that free speech and moderation issues weren’t central to the app’s initial design. “We weren’t thinking about this at all. We were thinking about building something that we wanted to use,” Dorsey said.

Nevertheless, decisions usually end up being made behind closed doors by a very small group of people. Companies then farm out the labor to either overseas moderation banks or programmable bots, or generously heap the work on their own platform’s user base. This leaves some users in that role to begin to detest the site that they frequent.

Yet, despite the collective efforts and investments that social media companies have made to tidy up their dominions, many users still stumble upon unsavory content or have their appeals go unheard.

“Social media platforms are vocal about how much content they make available, but quiet about how much they remove … sites also emphasize that they are merely hosting all this content, while playing down the ways in which they intervene.”

Online Communities and Scale

Back in the early days of the World Wide Web, logging on required a significant amount of working knowledge — like coding and local networking. Compared to today’s standards, communities were small and self-regulated.

During the mid-aughts, improvements to graphical user interfaces (GUIs) and the expansion of broadband infrastructure made it easier for tech novices to get up and running. Online communities grew exponentially.

Today, keeping people logged in while providing safe moderation is the ultimate balancing act. “Moderation is there from the beginning, and always,” Gillespie writes. “Yet it must be largely disavowed, hidden, in part to maintain the illusion of an open platform and in part to avoid legal and cultural responsibility. Platforms face what may be an irreconcilable contradiction.”

Economics of Moderation

In September 2006, Facebook transformed the online experience when they implemented their algorithmically driven news feed. The shift in format incentivized populism and many site models followed suit. With artificial intelligence at the helm, social media platforms direct users towards trending posts in an effort to keep them logged on, regardless of their content — even if that means the perpetuation of hate speech and radical ideologies.

Following the rise of “fake news,” legitimate concerns of foreign meddling in the 2016 election and the public’s growing skepticism of social media’s influence, Facebook is finally re-evaluating their algorithms. However, CEO Mark Zuckerberg and his team still continue to favor content that generates site traffic over an improved user experience.

If these companies fail to act responsibly until after the point that a response was necessary, should they be immune in the courtrooms of our nation?

Trump and Twitter

Social media had a monumental task in tactfully tackling the unique issues presented by Trump. The once-reality television icon turned single-term president commanded an audience of over 88 million subscribers on Twitter — the company most responsible for finessing the celebrity-in-chief.

Trump’s working relationships brought the loopholes exploited by these social media providers to the forefront of public criticism. The nation watched as the industry sparred with the irreverent and outright combative account holder as he stretched their policies. When other users might have been silenced, suspended or banned indefinitely, Trump stayed at the peak of his pulpit, with all the major providers allowing him a platform.

Despite being competitors, Gillespie notes that social media providers work to maintain a consistent level of decorum in their censorship and community standard if only to appease investors, quiet criticism and avoid lawmakers. These policies are often traded and borrowed from one platform to the next.

Throughout his presidency, Trump took aim at Section 230. He even issued an executive order to overturn it and then tied the policy to pandemic stimulus checks in tweets.

His ire hit a crest when Twitter added a feature to “fact check” his posts, the argument being that if platforms add or amend the content of a user, they then become publishers and therefore subject to legal proceedings. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg wasn’t happy with the move by Dorsey and criticized Twitter’s decision. Regulating one player means regulating them all.

Trump’s executive order, once available online, has since been taken down. Days after the insurrection, FCC Chairman Ajit Pai announced the commission would not move forward with the directive to amend Section 230.

Now you might wonder why Trump would want to go after social media platforms. Wouldn’t shutting them down hurt him? Here’s the thing: if forced to commit to a distinction, Trump is betting that social media will side with the “safe harbor” protections that align them with telecommunication companies over traditional publishers because it’s more cost effective.

Again, under the current law, these companies are sheltered in both assuming and relinquishing their moderation responsibilities. If they’re forced to put themselves in a particular class, which is why legislators asked Zuckerberg, “Is Facebook a ‘Media Company?’” ad infinitum during the Cambridge Analytica hearings, Trump is betting they’ll evade responsibility rather than assume it — in other words, act like him.

Unlike other celebrities with a mega subscriber base, Trump regularly violated the clear policies in both the platform’s “community guidelines” and “terms of service.” The list of these infractions is too great to dive into for this exploration. However, Vox recently put together an article documenting his hate speech — both online and in real life.

Twitter received significant criticism for not banning @realDonaldTrump sooner. But the events of the January 6 Insurrection finally saw social media take action.

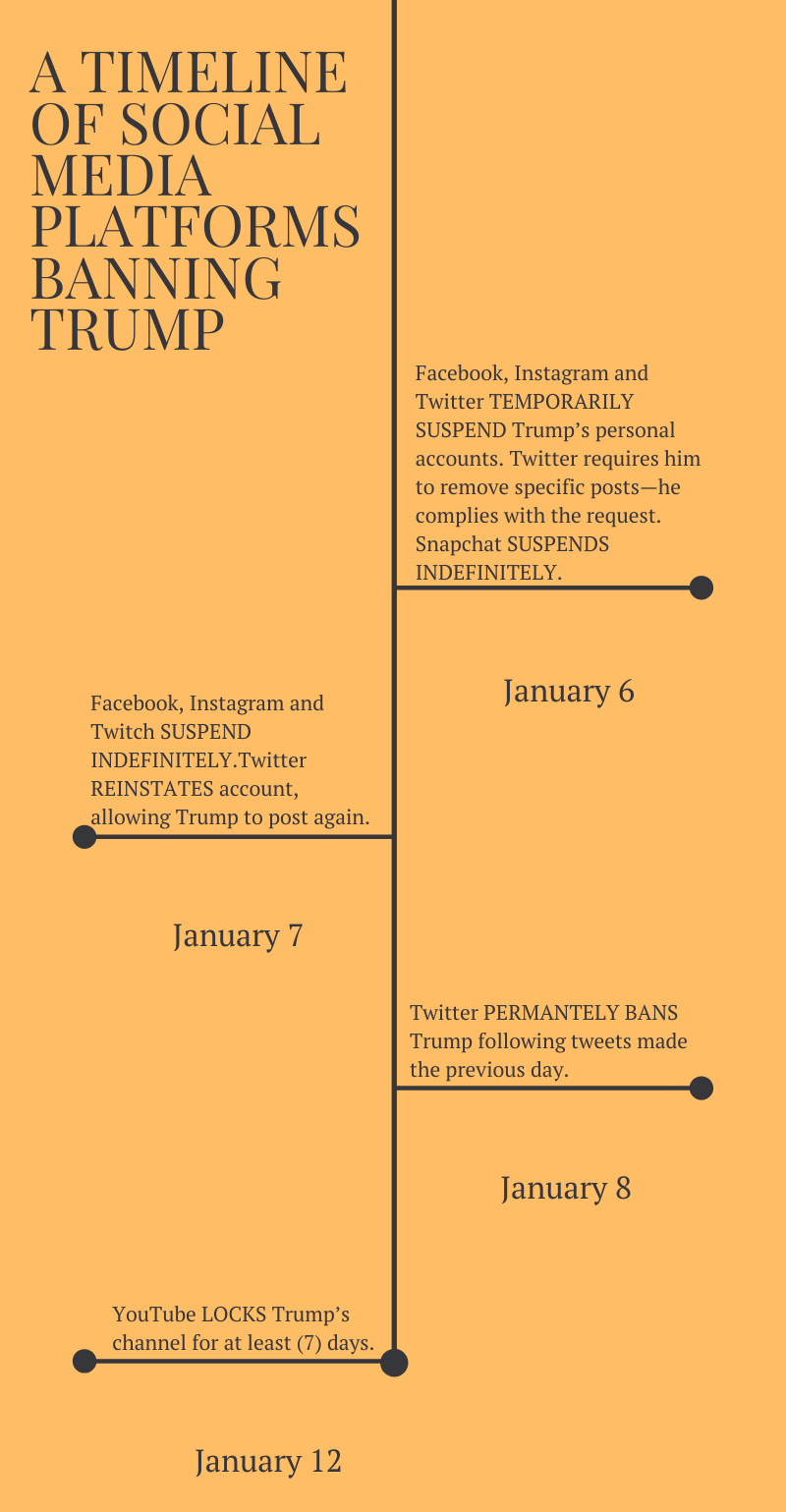

Graphic by Yusra Shah, 14 East

A few interesting things happen in this progression. To begin, within 72 hours of the insurrection, the most prominent platforms took unified action to boot the president from their respective websites. Curiously, minor players, like Twitch and Snapchat, took the most serious and swift action — YouTube waited a week to lock his channel.

As this was happening, Trump instead attempted to tweet via the government’s presidential account. This effort was quickly locked down by Twitter, who cited the forthcoming administrative transition. While the president was silenced by the free market, he still had the professional privilege of issuing White House press statements.

This instance illustrates that social media companies make coordinated efforts to align with one another when it’s to their benefit. Had Twitch continued to welcome Trump, it would open them up to potential social backlash and create a distinction worthy of disrupting legal precedent by displaying a willingness to accommodate controversy.

The Future in an Unchecked System

We no longer need to wait around and see what these policies can do because we already know how they affect us and society at-large.

It’s easy to say social media companies should have seen the chaos coming because they’re facilitating it. But those who seek to incite violence and instability always find a way to connect — if they get kicked off 4chan they go to 8chan. Rename, reshape, regroup, whatever. But that’s one issue.

It’s another issue when these sites reinforce popular content in order to increase site traffic. An unchecked system means automated radicalization on places like YouTube and Twitter. As a society we need to question whether capitalism makes that acceptable or not.

In order to do so, The United States needs to critically revisit the protections and classifications of ISPs and digital intermediaries for the modern era of telecommunications. We must champion legislation that promotes responsibility and stewardship as our arenas of sociopolitical discourse migrate online — without it, we will continue to risk our union’s survival.

Header image by H.C Stephens

NO COMMENT