Academia goes through periods of transition, but rarely are they fast and absolute. As the U.S. adjusted rapidly to uncertainty in mid-March, DePaul students and faculty dove headfirst into this uncertainty in the form of remote classes and are still trying to adapt.

Because of the coronavirus pandemic, some of the usual safety nets relied on during transition were not there, like seeing students or being able to seek help in person. This leap was taken out of necessity by most other universities in the country, but unlike many universities, DePaul’s transition started during finals week under the quarter system. So, how prepared was DePaul to take this plunge and how have classes been executed?

Figuring Out Finals Week

Before DePaul dropped the March 11 email announcing all Winter Quarter finals would be conducted remotely, Interim Provost Salma Ghanem contacted the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL), the support system faculty have for designing and conducting classes, to see if they were equipped to shift Spring Quarter classes online. They were prepping to make this move when they received word that higher-ups wanted to move finals online, according to Sharon Guan, assistant vice president of CTL.

“So my question is, finals online, is that a Plan B or Plan A? Because we’re still monitoring the national news,” Guan said. “And I was shocked when I was told this is Plan A.”

James Moore, the director of online learning for the Driehaus College of Business, said that his college had already been having conversations on how to keep classes going if students felt uncomfortable coming to campus.

“We transitioned to methods in which we could teach a regular class, but accommodate for students who wouldn’t come,” he said.

The first thing Guan did was record the percentage of faculty who had not registered their courses on the learning management system, Desire2Learn (D2L), for each college and alert their deans so they would have some measure to gauge their faculty’s basic comfort level. In colleges that are less likely to require online submissions, such as The Theatre School and the School of Music, this number could be as high as 60 percent. Meanwhile, Moore said that only seven business courses for Winter Quarter did not use D2L.

CTL also helped the provost to offer suggestions to faculty for finals, like assigning essays instead of tests. In two days, they contacted and implemented Respondus, a high-stakes testing system that locks a tester’s browser and uses the webcam to scan their physical environment, for classes that needed monitored remote testing.

“We immediately gathered all of the staff together and identified the things that faculty must learn. Like what’s the most fundamental essential thing that they need to do?” Guan said. “And based on that, we came up with webinar topics.”

Within 24 hours, they posted a list of offered webinars and CTL’s faculty development team began working on them. The webinars were initially capped at 30 people, but the demand exceeded that, so they changed the limit to 50 people. Still more faculty were interested, so they changed it to 70, and then 80. The team members leading webinars started messaging their colleagues on Slack for backup because they couldn’t get to all the questions in the Zoom chat.

As professors swept their finals online, students also rushed to move their lives online. DePaul gave students living on campus less than two weeks to evacuate with their belongings while they finished the academic quarter.

“It was pretty stressful because I had finals that week, I still had in-person classes to go to, as well as the fact that at first I didn’t know where I was going to go,” Ava O’Malley, a sophomore journalism major and 14 East contributor, said about her housing transition.

A friend invited her to stay with them in Lincoln Park, but the rent was too high. She felt defeated and started to prepare to move back to her family home outside of Cleveland, but movers backed out when they found out a DePaul professor had tested positive for coronavirus. Her parents rented a big car that could fit all of her stuff last-minute and drove to pick her up.

These complications of moving affected O’Malley’s state of mind during finals week.

“I had an oral exam with my Spanish professor which I ended up completely forgetting about because I just had so much on my mind, but she was actually really understanding,” she said.

Transitioning Full Courses

After jumping the hurdle of finals, DePaul students, faculty and staff had one week to prepare for a Spring Quarter unlike any that had occurred previously. Faculty scrambled to change their courses to a totally new virtual format.

Guan said that approximately 800 faculty members have officially been trained to teach online in the last 12 years, 40 percent of the teaching force. The training program’s workload is equivalent to a three-credit course and comes with a $1,500 stipend if the work produced passes evaluation. It’s a three-step process: first, faculty take a hybrid course to learn the pedagogy of online learning and see it modeled.

“It’s what we call a backward design process, having a goal in mind and then knowing how to assess and then it goes to, ‘How do I deliver teaching in order to achieve all of these things?’” Guan said. “So it’s a complete rethinking process for faculty training.”

After learning how to think about an online class, faculty in the program attend a two-week intensive where they create an online course with an instructional designer from CTL. Then, the course is evaluated according to a nationally standardized rubric for online learning.

Though 40 percent of faculty have been through this process, the representation of faculty members in each college varies, as does how often faculty actually put these skills into practice. Moore said that the School of Business usually conducts 10 percent of classes online.

“So if you think about 600 courses a quarter, maybe 60 of those would be online,” he said.

To help faculty make this rapid transition to remote learning, CTL’s three divisions went into overdrive. While the faculty development team ran 52 webinars, the central support team that manages technology problems closed 984 support tickets in March alone and offered 252 quick tech consultations, 5.6 times the number from the previous month. The instructional designers, who normally build a set amount of courses on D2L in advance, logged 1,185 consultation sessions with faculty in addition to working on 169 course development projects. Guan noted in an update for Newsline that the College of Science and Health’s senior instructional designer had 44 faculty show up in his first virtual office hour.

Guan estimates their workload more than quadrupled. The department worked 800 extra hours in March — employees worked two weekends at the beginning of the transition and could not take a full weekend off until Easter weekend in mid-April. Though Guan said her teams are tough, she remembers two meetings with the heads of each of CTL’s three teams where three out of four people cried.

“I think the major challenge is actually finding a way to channel the workflow,” Guan said.

Because they were being flooded with requests from all areas, they had to develop a chain of communication to make sure things were being completed. Guan instituted a color-coding system in Slack to show each person’s level of swampedness, as well as informational and tech meetings at the beginning of each day to make sure the teams were on the same page.

In addition to the sheer volume of classes that needed to transition, faculty and staff also had to grapple with making the remote learning environment work for students.

Before Spring Quarter started, the School of Business online team told their faculty that all classes would be asynchronous, or would not require all students to meet online at one time. If professors wanted to have Zoom sessions, they could not be required.

“If you think about students who may be parents, who have jobs, they’re looking for that flexibility and convenience,” Moore said.

In addition to expanded flexibility, they were worried some solutions that the school had used previously, like Zoom during the Polar Vortex, just wouldn’t work for everyone. Most online classes were already taught asynchronously, but again, not all business faculty have been trained to teach online or recognized the strategic organization it requires.

“I’ll be honest, I think there were very few faculty who were aware of what they needed to do,” Moore said.

However, he thinks that most faculty, being business-minded, were ready to tackle the challenge to keep courses afloat.

Most other schools within DePaul have left the asynchronous versus synchronous question up to individual faculty members. The advantage of synchronous Zoom classes are obvious: teachers and students can see each other, have in-the-moment discussions and the teacher can avoid putting lots of content online. However, Zoom classes might not engage students in the same way as physical environments and without proper security measures, the chat room can be intruded by Zoomboomers, who can and have inflicted lewd acts and racial slurs on DePaul students.

The hastiness of the transition lets more stuff like this slip through the cracks, which is why some online learning educators have pointedly labeled what’s happening now as “remote learning,” not normal online learning.

“It essentially says, we’re doing something in extreme circumstances, this class may not be the best, but we’re doing this to meet a particular need,” Moore commented on the language choice, though he said that the business school’s all-asynchronous classes would qualify as good online learning.

From the Student Perspective

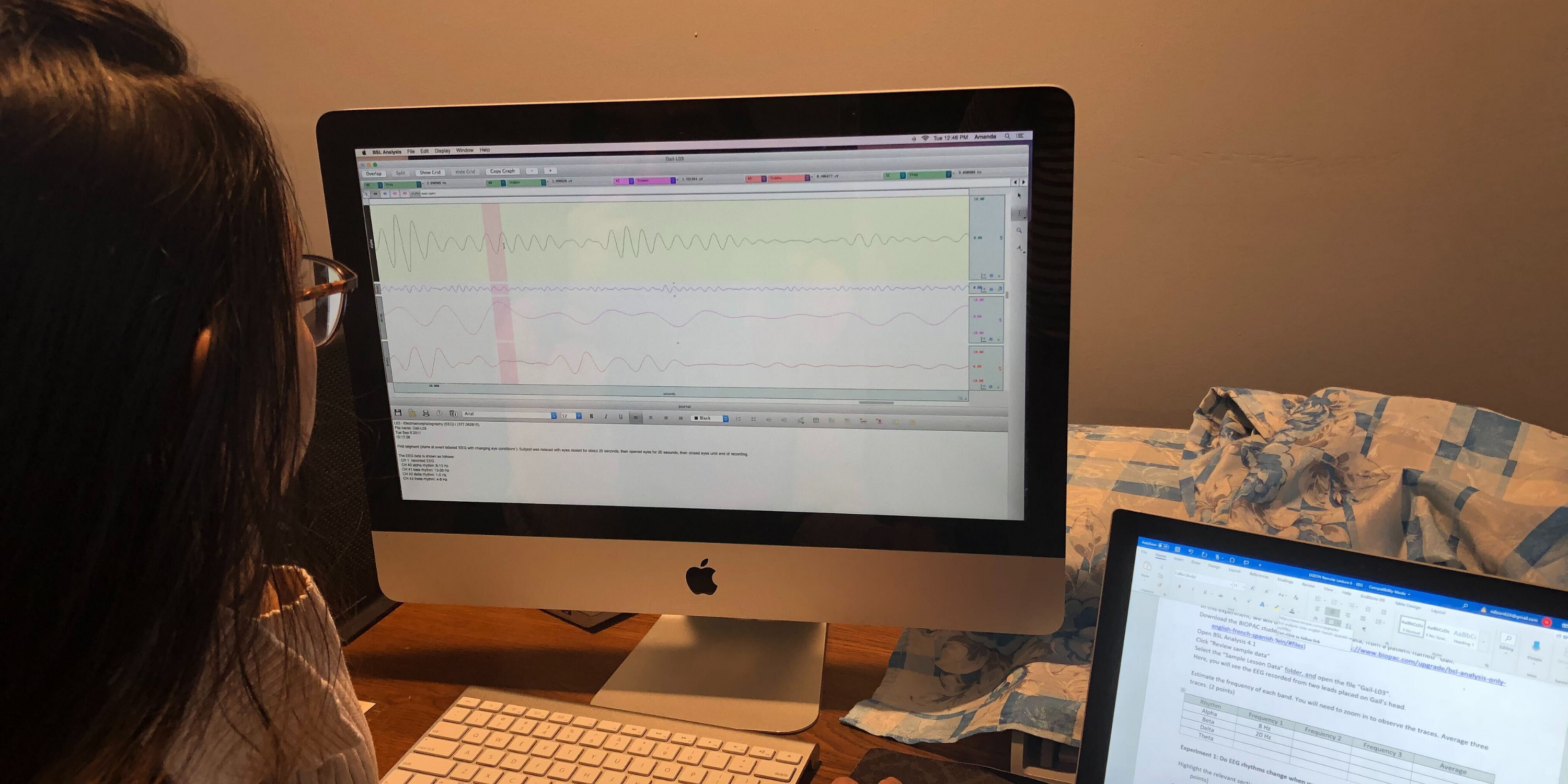

Photo courtesy of Ava O’Malley.

DePaul’s students have similarly mixed backgrounds in online learning, but unlike faculty, they might no longer have a steady source of income or housing. These external stressors affect their ability to learn.

Alexandra Acain, a rising senior studying sports communication and journalism with a minor in photography, finds remote learning tolerable.

“I feel like I’ll come to a point in one of my classes where I’m not really satisfied with my grade and I’ll have to somehow repeat a course or two to remedy my progress,” she said.

For Sydney Van Sickle, a part-time graduate student in history and a full-time eighth-grade teacher, the quarter so far has been surprisingly rewarding.

“I had questioned whether I should do it [take a class this quarter] because I didn’t know what sort of emotional toll this would take on me,” Van Sickle said.

Her family and colleagues said that class could be a lifeline to the outside world while her job became more stressful.

“I have found it really refreshing to get on Zoom with people near my own age and kind of, I don’t know, stimulate my brain a little bit,” Van Sickle said.

O’Malley, after her abrupt change in housing, said that she’s had to get organized and develop a routine to stay focused. She won’t let herself sleep past 9 a.m. and completes all of her schoolwork at her desk instead of her bed.

“I’ve definitely found it very hard to be motivated,” O’Malley said. “Even now, I think I just can’t get my brain in this academic mode because I’m just so far removed from campus and all of my classmates and my form of my learning environment.”

Acain said though her classes have been manageable, adapting her photography work has been challenging, and she misses in-person interaction.

“I kind of miss printing out work to post on the critique walls and then having my other classmates and my professor look at my work,” Acain said, “and actually tell me what I did well on my projects or what I can improve.”

Van Sickle appreciates that her history instructor decided that a Zoom session doesn’t hold the same luster as an in-person meeting. The instructor shortened some of the in-class time and replaced it with discussion boards. Her biggest challenge is staring at a screen to read one e-book a week for class, which she would normally find print copies of in libraries.

On his end, Moore has heard from students who have wanted to express their gratitude that classes have continued to run and allowed students to finish their degrees or keep on track with their course order.

“I’m also hearing from some folks that their lives have become increasingly more stressful,” he said.

Indeed, some students feel like their classwork is overburdensome or no longer worth the price of admission in the online format. Students have been circulating petitions for DePaul to provide refunds and financial safety nets due to extraordinary circumstances, some of which have been established. Two students filed a class-action lawsuit against the university this month for partial reimbursement, claiming that DePaul is failing to live up to its academic standard. Students can now apply to get $500 through the CARES Act, which stipulates applicants completed the FAFSA and enrolled in classes supposed to be face-to-face as of March 13, but some students found the wording of DePaul’s form confusing.

Moore said that he understands the impulse for wanting things to be easier, especially earlier in the quarter when the transition was starting, but that it would not serve students in the long term.

“I think we need to make sure that our quality is the same, so that a student who graduates is going to be proud of their degree and they’re not going to feel that we gave them an easy quarter,” he said.

O’Malley and Acain note that some of their professors have tried their best to provide materials and be more lenient with deadlines, though the workload has barely changed. With the DePaul Faculty Council’s approval of creating a Pass/Fail option, which became a Pass/D/Fail option when enacted by Interim Provost Ghanem, students have some room to adjust their workloads without affecting their GPAs. However, completing enough work at a high enough level to still pass is dependent on professors, their assignments and grading systems.

Guan teaches as an adjunct in the modern languages department, where a student has told her that classes have been providing a sense of normalcy and distracting them from the ever-unfolding news. She said she receives daily offers for help and kudos from faculty for the online teams, which energizes them.

In early April, they polled faculty in a CTL newsletter on how optimistic they were about teaching remotely. Only 57 people responded, but results were more promising than expected.

“Twenty-eight of them said they’re very optimistic regarding their ability to teach online this spring and 21 said they’re somewhat optimistic,” she said.

The Possible Paths Forward

At this point in the quarter, as Guan said, “We are over with the house-on-fire phase.”

Faculty who were supposed to teach online for Summer Quarter were given a chance to back out if they did not want to teach remotely, and then the Center for Teaching and Learning started to take on remote courses to build.

“You really cannot build as we go during summer because the class is a day after day after day schedule,” she said, referring to DePaul’s five-week summer intensive classes that normally have sessions several days a week.

Moore said that the School of Business has planned for summer and is preparing for “multiple futures” that could happen after that, depending on the guidance of health, government and DePaul officials. The school is conducting a survey at the end of quarter to receive feedback on students’ learning experiences.

“These will be questions along the lines of, ‘What computing device do you have now that you can use?’” he said.

In addition to reflection, he also pointed forward to new technologies or solutions people might realize are more efficient or flexible after going through this pandemic. In his internet marketing class last quarter, he taught students in a tri-modal room, which projects a video grid of online synchronous students on monitors in the front and back of the room so that both the in-person students and teacher can see them and vice-versa.

“I can maintain eye contact with both of those audiences. So the beautiful thing is, a remote student would present, the students in class would see that, they would interact, they would ask questions,” Moore said. “And that’s something that we’re developing for the future as a way to sort of meet the changing needs of students.”

Acain said that the key to remote learning is being patient.

“I don’t exactly want to be too worried because I know that this thing will be passing soon,” she said.

The next phase of the future for education may be less isolated, but just as complicated. Universities across the globe are devising new strategies to recreate some form of interpersonal connection for students, from rotating block classes to low-capacity dorms to keeping lectures online. DePaul is no exception, so Fall Quarter will likely require more on-the-fly adjustments. The question that remains is, how do you partially flip a switch back off?

Header image Courtesy of Natalie Dizon

NO COMMENT